And so, after a rather longer period than I anticipated, we come back to the beginning. This whole series was prompted by my booting up Curse Of Monkey Island back in October of last year, and wondering: why was Curse the last high-profile 2D point and click adventure game that LucasArts made? Was the genre an evolutionary dead-end? Was the lure of 3D graphics — which were exploding in 1997 thanks to the Voodoo accelerator card — too strong to resist? And considering Curse in particular, I wanted to get a bit more context on just why LucasArts had abandoned their previously wildly-successful genre at precisely the moment they’d managed to usher it to its apotheosis — because Curse is absolutely fantastic.

My (admittedly hazy) recollection is that this wasn’t exactly a popular opinion to have at the time. Said popular opinion tended to rank Curse in a distant third place behind the first two Monkey Island games, and one of the things I do definitely remember is a certain amount of griping from the gaming media that the 2D graphics made it look old-fashioned; 1997 was around about the time when everything was making the jump to 3D whether it was a good idea or not, and so Curse sticking to its guns was seen by some as an unforgivably antiquated approach. The big irony is that now, in 2021, if you stick Curse next to any 3D game that was released in 1997, the 3D game will be a mess of jagged edges and pixelated textures while Curse hasn’t aged a single day. It remains absolutely the best-looking adventure game ever made; even the modern adventure game renaissance hasn’t managed to produce anything that matches the colourful, stylised art and animation of Curse. If you’ve played the previous Monkey Island games it is a bit of an adjustment to see the previously regular-sized Guybrush Threepwood transformed into a lanky giant, and the fact that everything is made out of cartoonish curves — I don’t think there’s a single straight line in the game — also takes a bit of getting used to. I thought Curse was a weird looking game back in 1997, but time has proven the value of its art direction.

The technical advances made to allow the SCUMM engine to take advantage of better technology are also impressive. Starting from Last Crusade in 1989 and going all the way through to The Dig in 1997, it’s obvious that all of LucasArts’ adventure games were based on the same engine; they (mostly) all use the same font and the same mouse cursor, and while the later games improved on the art and animation and experimented with the interface it never diverged so much that the game was unrecognisable as a SCUMM game. Even in Full Throttle, which spliced in a whole other game engine from Rebel Assault to do its on-rails motorbike bits, it was easy to see which parts of the game were driven by SCUMM and which were not.

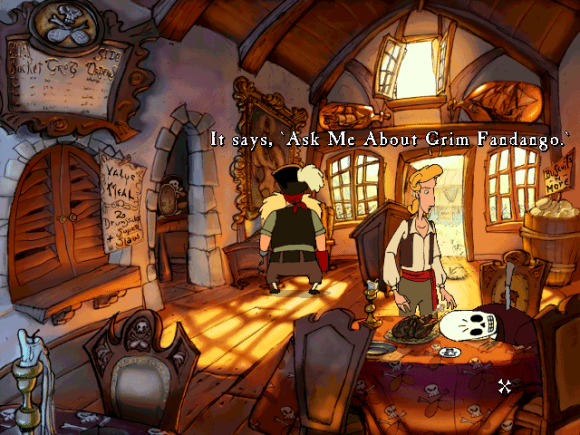

But while Curse doesn’t jettison SCUMM convention entirely, keeping the conversation interface and the coloured subtitle text that indicates who is speaking, it’s otherwise impossible to tell that it’s running on the same base technology as all of the other LucasArts games. It’s the first (and only) LucasArts adventure designed to run at a resolution of 640×480 — this sounds laughable today, but it represents a near-doubling of the number of pixels1 on the screen, allowing for much richer environments, backgrounds and animation detail. I love the classic pixel art of Loom and Secret of Monkey Island, which did so much with so little to work with, but The Dig pushed that art style about as far as it could go and Curse is a quantum leap forward that would have changed the entire 2D adventure game genre if it hadn’t died about two seconds after it was released. The iMUSE dynamic music system has been beefed up to work with Michael Land’s brilliant CD-quality soundtrack (see the Puerto Pollo theme and the Barbery Coast theme for two of the standout tracks… look, just go and listen to the entire thing, you’ll thank me later) and the truly ridiculous amount of voiced dialogue meant that Curse was also the first LucasArts adventure game to ship on two CDs rather than one. Unlike a lot of prior efforts which threw in pre-rendered videos and voice tracks just because they had the storage space going spare, Curse actually needed all of it.

Speaking of voice acting, this was the first thing that jumped out at me on getting past the introduction and into Curse proper. At this point LucasArts had been fully voicing their games for several years starting with Day of the Tentacle in 1993; the novelty has long worn off, so I wasn’t expecting Curse to make much of an impression on me in that regard. However, I was not prepared for just how much of it there was. Curse has more conversation options — and thus more voice acting — by about a full order of magnitude compared to prior LucasArts games. It’s a dramatic change in approach compared to Full Throttle and The Dig, which went to great lengths to stop you from talking to anyone and whose conversation systems were largely functional gameplay mechanisms with a few jokes scattered around the edges. Curse instead views its conversation interface and voice responses as the primary delivery mechanism for its humour, and so it hits you with joke after joke after joke. There are characters in this game where one conversation option with them advances the storyline and the other four lead to sub-trees of nothing but jokes. And the jokes are actually good! Sure, there’s the occasional line that falls flat on its face, and whether others land depends on how much you enjoy terrible pirate puns, but I think Curse’s hit rate is higher than any other LucasArts game outside of the original Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle.

(A good example of just how ridiculously in-depth Curse’s voice acting is can be found in the theatre in Puerto Pollo. Guybrush can barge into the theatre while the actors are rehearsing to hear a selection of gloriously awful jokes mashing up classical plays with braindead modern entertainment trends. Most games would record one or two lines for this and then switch to a generic “sod off” response from the actors as they get tired of Guybrush’s constant intrusions. Not Curse, though; Curse has fifteen or twenty of the things that you can cycle through in succession, and then when the game is finally out of jokes it switches to a procedurally-generated set that, while admittedly not very good, is still far more effort than I expected them to put in to a location that other games would treat as an afterthought. Because who is going to see this? Who is going to actually go to the trouble of cycling through all that dialogue for no gameplay benefit? Curse dedicating so much effort to making the player laugh is a development philosophy that’s entirely at odds with modern achievement-driven game design, which is why it’s also a very refreshing thing to experience in 2021.)

The clever writing is also helped along tremendously by Dominic Armato’s performance as Guybrush. In a game so stuffed full of dialogue, where the main character is providing one half of every conversation and is also giving wry, self-aware commentary on everything that he’s doing, it would be easy for Guybrush to seem smug, grating and/or tiresome, a little like Boston Low eventually did in The Dig. It’s largely thanks to Armato that he does not, and there’s also many jokes that rely primarily on his voice acting talents in order to sell them, like El Pollo Diablo or the excellent segue into a William Shatner impression when he’s reading from the ventriloquy guide. The rest of the voice acting in Curse is extremely high-quality — the Barbery Coast pirates are astonishingly good — but even so Armato manages to stand out with a performance that literally defined the character; it’s unsurprising that he went on to spend a large portion of the next fifteen years voicing Guybrush, because it’s impossible to imagine anyone else doing it now.

From an actual mechanical perspective, though, it’s interesting that despite LucasArts having voiced their games for nearly half a decade now, Curse is the first one to leverage its voice acting as an informal hint system. If you use the wrong item on the wrong object in any previous LucasArts adventure game, you get a pretty generic response from the protagonist: “That won’t work.” or “I can’t do that.” or in Full Throttle’s case “I’m not putting my lips on that!” This was mostly a historical compromise forced on LucasArts because they didn’t have the resources to write and then voice unique lines for every interaction, although there’s also the factor that this wouldn’t have seemed like the wrong thing to do at the time because it had never been done differently. Thanks to its vastly increased quantity of voice acting lines, though, Curse can afford to be much more specific. For example, early on in the game you pick up a pair of scissors, and a little later on you run across a sawhorse-type thing supporting a barrel of gunpowder. You need to move the gunpowder barrel to another location by rolling it, but it’s held firmly in place by the sawhorse, so the next logical step is to try and saw the sawhorse to bits. At this point in the story the only sharp item you have in your inventory is a small pair of scissors, but thanks to the series’ prior record of Adventure Game Logic (hello, monkey wrench puzzle) it’s possible that these might still do the job. So you try using the scissors on the sawhorse, but instead of that generic “I can’t do that” line, Guybrush instead responds with “I can’t saw the sawhorse with scissors!” Okay, great! That means I must be able to saw it with something, and that I’m on the right track here; I just need to find the right item.

These special hint voice lines aren’t in place for every possible interaction, but they exist for enough of them that the impact of Curse’s at-times utterly obtuse puzzles is softened to the point where they are bearable. Coming to it 24 years later, I think the puzzle design is definitely the weakest link in a game that’s otherwise got stellar production values across the board. That is not to say that they are bad — by the standards of this series alone Curse still ranks in the top fifty percent for puzzle consistency, and if we widen the comparison out to its mid-90s genre contemporaries it’s a shining paragon of internal logic. It does feel a bit too variable, though, with a few too many puzzles where 90% of the steps make perfect sense and then the remaining 10% were designed by an alien or something. Particularly enraging puzzles this time around were using the magic wand on the top hat to get the ventriloquy book — this is especially awful because the top hat is just another prop that’s camouflaged in a backstage room in the theatre that’s absolutely full of props — and catapulting the corpse of the groom through the hole in the wall. This latter one is pretty emblematic of Curse’s bad puzzle design habits; you can see that there’s a boarded-up hole in the wall that you can pry the boards off of, and you can see that the groom’s skeleton is on top of one of those spring-driven beds that folds away into the wall, which is nailed down to the floor. Removing the nails is another obvious interaction (once you have the crowbar, anyway), but what’s not obvious at any point of this process is why you are doing this; the eventual outcome is so cartoonish that there’s no possible way to predict it before you do it.

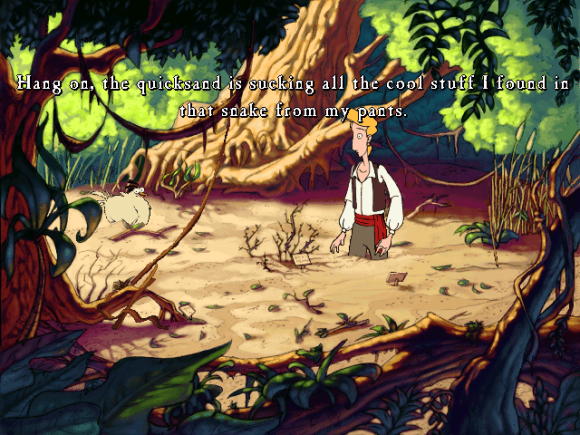

Fortunately those puzzles are in the minority. While the puzzle design in general might be nowhere near as elegant as the ones in Secret of Monkey Island or Day of the Tentacle, and while I had significantly more trouble with the back half of the game on Blood Island, which I remember far less well than the opening episodes in Puerto Pollo, I only had to resort to a walkthrough twice. And to be completely fair to Curse, while the logical aspects of its puzzle design can be a bit lumpy that’s usually because it is (once again) using them as an excuse for some absolutely cracking jokes, which is a tradeoff that I’m willing to accept as long as it doesn’t completely compromise the game the way it did in Sam & Max. I was very happy to see the return of inventory humour with the python/quicksand puzzle (it last appeared in Day of the Tentacle), and there’s an absolutely brilliant meta-joke where Guybrush drinks what is essentially poison to get interred in the Goodsoup family crypt. He passes out in the hotel bar, and “SOME TIME LATER…” the gravekeeper turns up and comments on how he thought you couldn’t die in LucasArts adventure games. “Perhaps they’re trying something different”, drawls the bartender, and so Guybrush is duly hauled away and dumped inside the crypt; the credits start to roll, complete with a “You scored 0 out of 800 points” riff on Sierra adventure game death screens, and get a surprisingly long way before Guybrush loudly interjects that he isn’t dead. Just like the original Monkey Island, Curse is at its best when it’s taking the piss out of adventure game tropes; it takes a lot of finesse to accomplish this without falling victim to the same bad design it’s supposed to be mocking, but Curse just about manages to successfully thread that needle.

I haven’t really talked about Curse’s plot or story structure yet, and I suppose I should even though I see it as somewhat irrelevant — the story is there largely as a framework to hang the pirate barbershop quartets and lactose-intolerant volcano gods off of rather than existing in its own right as an actual coherent thing. Curse starts a little while after Monkey Island 2’s infamously bad theme park ending, with a bit of hand-waving narration from Guybrush as to how he escaped and ended up adrift in the middle of the Caribbean. He washes up on Plunder Island, where his girlfriend Elaine is conveniently governor but who not-so-conveniently gets transformed into a solid gold statue after Guybrush gives her a cursed diamond ring. The voodoo priestess (another source of great meta-jokes about the series) tells him that the only way to break the curse is to replace the ring with an uncursed one of equal or greater value, and Guybrush quickly discovers that there’s one on Blood Island. So step one of his quest is to find a ship, a crew and a map to Blood Island; step two is to retrieve Elaine (who is stolen by pirates shortly after the game starts); and step three is to sail to Blood Island and find the uncursed diamond ring.

Curse is technically split into six acts, but most of the game’s content is found in just two of them, the Plunder Island and Blood Island segments. It unfortunately makes the mistake of frontloading most of its best content; I understand the value of making a good first impression on the player, but Plunder Island is so much better than Blood Island that it feels like a significant comedown once you leave the former and get to the latter. This isn’t because Blood Island is bad — it’s got a decent number of its own standout moments — but rather that Plunder Island is the bit of Curse that you can put up against any other adventure game in existence, including the original Monkey Island, and it’ll probably come off best. It is absolutely superb, stuffed end to end with memorable characters, excellent jokes and fantastic music, and there’s only one or two duff puzzles in the whole act. Things noticeably and immediately drop in quality the moment you leave, not least because…

…ugh…

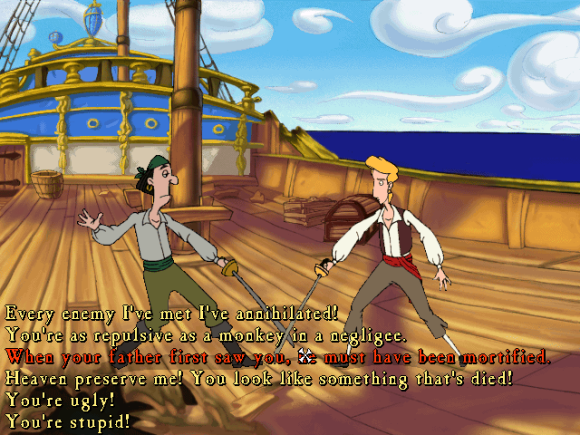

…we’re doing Insult Swordfighting again. Act 3 is the insult swordfighting act that has you sailing around the Caribbean fighting other pirates (complete with Pirates!-lite ship vs ship combat) so that you can upgrade both your ship and your insult repertoire to the point where you can take on the big boss who has the map to Blood Island. The insults and responses are rhyme-based now, but otherwise this act is identical to the insult swordfighting segment of Monkey Island 1, which was funny for about seven seconds back in 1990 and then merely incredibly, unbearably tiresome every time I encountered it after that. You can imagine how overjoyed I was to be asked to repeat the process for a full twenty minutes in Curse. (And honestly, it’s a mercy it’s as short as that.) This isn’t even a reference or a callback, it’s just the same joke repeated over and over again like a bad fucking catchphrase, which is something that Curse, for all of its series meta-humour, is otherwise remarkably good at avoiding. I wouldn’t give up the start of Act 3 for the world because it’s one of the best sequences in the game, but I could really do without the rest of it.

The game does pick up again once Guybrush gets to Blood Island, although it can’t match the highs of Plunder Island. Blood Island’s strengths are its astonishingly lovely artwork — just like Melee Island in Monkey Island 1 and Scabb Island in Monkey Island 2 it’s perpetually shrouded in night, which lets the art team do some incredible things with the lighting and colour palette — and a few excellent set-piece jokes. Its weakness is that it’s less goal-oriented than the Plunder Island section of the game, which split its objectives up into a series of manageable tasks and puzzles; Blood Island on the other hand has one objective — get the uncursed diamond ring — but your route towards it isn’t always clear and sometimes becomes so murky you end up going in circles for far longer than you really should. Regardless, it’s a perfectly good chunk of adventure game that only looks bad because it’s sat next to the much better Plunder Island segment. I know this because Curse’s finale comes perilously close to being almost as much of a wet fart as Monkey Island 2’s was, and while it is mercifully short enough that it doesn’t drag the rest of the game down (the puzzles here are so simple that you can be done with it in just ten minutes) it still serves as a timely reminder that things could always be much, much worse.

Still, this unevenness is something of a series tradition by this point; no game should try to emulate the confused, meandering structure of Monkey Island 2, but even Monkey Island 1 had a back half that was noticeably weaker than its front half. Curse falls somewhere in the middle, in that the majority of its content is rock solid but it occasionally feels the need to bamboozle the player with cartoon logic and take inexplicable detours away from the fun adventure game stuff into boring minigames and railroaded gameplay. Its standout features are its art, animation, music, voice acting and writing; that the actual puzzles are a little hit and miss only detracts slightly from how fantastic Curse is as an experience. I don’t think we’ll ever see a 2D adventure game with these production values ever again, because the modern genre is the preserve of small indie studios who don’t have anywhere near the resources required to pull it off. It needed a big budget studio like LucasArts, who had been making these things for ten years and whose development staff was at the top of their game in almost every single respect.

And that also answers the question I had a year ago, when I started this series: why did the 2D adventure game genre die out shortly after it produced what was arguably its finest game? Coming at that problem from 2020 it wasn’t immediately obvious, but now that I see Curse with the perspective granted from playing through the previous decade of LucasArts adventures the answer is pretty clear. Curse of Monkey Island goes above and beyond everything that came before it, but this came at a cost; the original Monkey Island was developed by a core team of around twelve people, but the credits for Curse list over seventy (the art team alone has ballooned from three people to twenty-four) and this is completely ignoring the voice actors and corporate support staff necessary for a company of the size of LucasArts in 1997. Curse did not sell well at all — 300,000 copies doesn’t sound all that bad until you remember that Full Throttle sold over a million — but even if it had, could it have sold well enough to justify such a large development team? I don’t think so. By the mid-to-late ‘90s game development was becoming increasingly corporate, and one thing corporations are very keen on is favourable return on investment2. Unfortunately by 1997 the cost of the development resources required to make an adventure game was starting to outweigh the amount of money made back from sales, and the market only continued to shrink after this — Grim Fandango sold even more poorly than Curse, indicating that perhaps the problem wasn’t with 3D accelerators after all.

So while Curse was far from a dead end in evolutionary terms, in terms of the market and the cold, hard financial truth that lies behind every video game it definitely was. You can’t make a game like Curse and also make money at the same time. Even today, in 2021, you probably still can’t. All of the things that so impressed me about Curse, like the vast quantity of throwaway jokes and voice lines, are also precisely the sort of things that would make anyone in charge of financing a game wince slightly before scrawling “REJECTED” across whatever formal paperwork was attached to their greenlight process. If the big-budget adventure game genre had to die, though, then I’m glad we at least got Curse of Monkey Island out of it before it shuffled off this mortal coil; whether it is the best adventure game ever made is debatable, but it is unarguably the best-looking, the best-sounding and the best-written one out there.

- It’s difficult to tell because ScummVM corrects for it so flawlessly, but I think The Dig and Full Throttle are running at 480×360. ↩

- Activision are currently pursuing this philosophy to an almost psychotic degree, with all of their internal studios save for King and Blizzard working on Call of Duty now; the sad truth is that putting a developer on CoD makes them significantly more money than if they put the same developer on Crash or Spyro. Of course this means that if CoD ever crashes and burns Activision is going to be completely screwed, but that’s very unlikely to happen any time soon. ↩

Curse of Monkey Island was the first adventure game I ever played and remains one of my favorites. One thing you didn’t mention: the absolutely wonderful music, especially the Monkey Island theme in the opening cutscene.

Re: the many voiced lines, even lines that weren’t explicit hints often at least suggested you were on the right track for something. Murray doesn’t provide you any information about what to do with the glued arm (“Get that thing away from me, you sick freak!”) but that he says anything at all suggests that it’s important.

It would be years before I was able to play the first two games, but it’s incredible how much damage the ending of LeChuck’s Revenge did. Both Curse and Escape devote a lot of flailing energy to try to make sense of it when both would have been better not having to even think about it.

I’m looking forward to your thoughts on Grim Fandango and the somewhat unfairly maligned Escape from Monkey Island.

Search for “iMUSE” in the article to see the notes about the music.

To expand on this, I know I gloss over the music a bit but that’s because if I started to talk about about it in any real substantial way this post would have been twice as long; the Curse soundtrack is one of my favourite videogame soundtracks ever and Barbery Coast might just be the cleverest piece of videogame music in existence.

A fantastic summation, and worthy conclusion to what’s been a great series of posts here Hentzau!

“ I don’t think we’ll ever see a 2D adventure game with these production values ever again, because the modern genre is the preserve of small indie studios who don’t have anywhere near the resources required to pull it off.”

I’ve been wondering if perhaps Netflix, with their recently stated push into interactive content could pursue this. Because they have the economy of scale, they could certainly provide the resources to make it happen.

Netflix certainly have the resources, but resources alone don’t make a good game — if they did, Crucible wouldn’t have been unreleased and then thrown into the garbage and I also wouldn’t be currently getting a daily laugh out of reading about all of the new bugs and exploits in New World.

Also, this *might* not be the conclusion. After I put this post up a “friend” gifted me Escape From Monkey Island on Steam, so now I feel an obligation to play through both that and Grim Fandango. Dealing with the tank controls will take a long mental run-up though, so it’ll probably be a couple of months before I get around to it.

Why not play the remastered Grim Fandango, which removes the tank controls and even adds in a conversation that didn’t appear in the original release due to a bug?

You can see the optimal points in the adventure scene of today. 2d graphics simply don’t scale cost-wise and generally need to be done at low res to be economical. 3d graphics scale much better, and can even be used to create pseudo 2d if the effect is desired.