Prior to playing it for this series, I would have sworn that Full Throttle belonged firmly in my “unplayed” category of LucasArts classics. “Unplayed” isn’t an exact description, as I did have access to most of them at the time and the ones that I didn’t I’ve since picked up on GOG, but anything in this column I’ve not played for much more than twenty minutes — the amount of time it takes to boot it up, think “That’s neat!” (or not1), and then immediately forget about it for the next decade or three. In Full Throttle’s case I had very distinct memories of playing through the opening biker bar segment three or four times and absolutely nothing after that, since I hadn’t played past that point.

This made the uncomfortable sense of deja vu I was getting all through the first half of the game rather odd. This was the first time I’d experienced the tiresome Road Rash puzzle and the canyon jumping and the getting-through-the-minefield section, wasn’t it? The further I got into Full Throttle the more ancient memories were disinterred and the more uncertain I became that this was my first time through, but I put that feeling at the back of my mind. After all, we live in a miraculous age where full playthrough videos of nearly every single game in existence are available with just a quick Youtube search, and it was very possible that I’d just seen one of Full Throttle and that’s where these false, fleeting memories of having played it before were coming from.

That rationalisation lasted me all the way up until the demolition derby “puzzle” towards the end of the game, at which point it hit me like a sledgehammer: I had played Full Throttle before. I’d finished Full Throttle, for god’s sake, and the reason I knew this for certain now was because I remembered getting just as frustrated with the opaque objectives and terrible controls and physics of this segment as I had almost twenty years ago. It’s just that unlike the other LucasArts adventure games — some of which I’d last played long before I played Full Throttle for the first and only time — there were no half-remembered details, no stand-out moments that stuck in my mind. I’d simply forgotten the entire thing, and for good reason: it’s incredibly forgettable, one of the most middle-of-the-road adventure games ever made. Partly this is a result of the theming — I am incredibly disinterested in bikes, bikers, heavy metal and the open road — but mostly it’s because of the way Full Throttle has been made.

We’ve seen that LucasArts liked to experiment with their adventure game design to try and keep the format from becoming stale, but even by those standards Full Throttle is quite unlike anything that has come before it. Released in 1995, it was the first LucasArts adventure to properly make the jump from floppy disks to a CD-ROM, which says something about the era: this is a time when CD drives are becoming commonplace and so FMV adventures are absolutely everywhere, and Full Throttle feels in part like an attempt to fuse the LucasArts adventure game style with the more constrained, cinematic gameplay of FMV adventures. Full Throttle puts far less emphasis on travelling around different locations and picking up inventory items that you have to use to solve puzzles — i.e. what LucasArts adventure games have mostly been doing up until this point, Loom excepted — and much more on participating in a more-or-less linear series of impressive (for the time) audio-visual experiences that, if you squint a bit, might pass for puzzles.

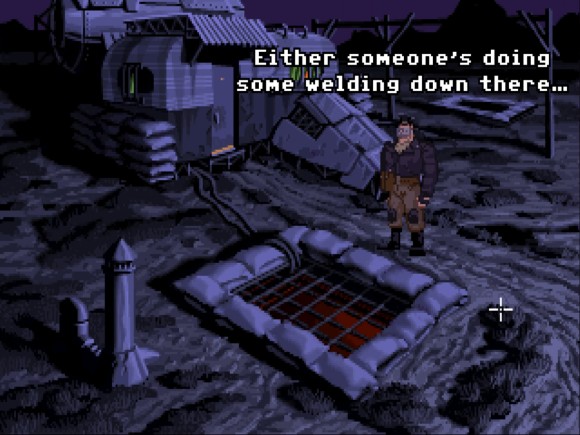

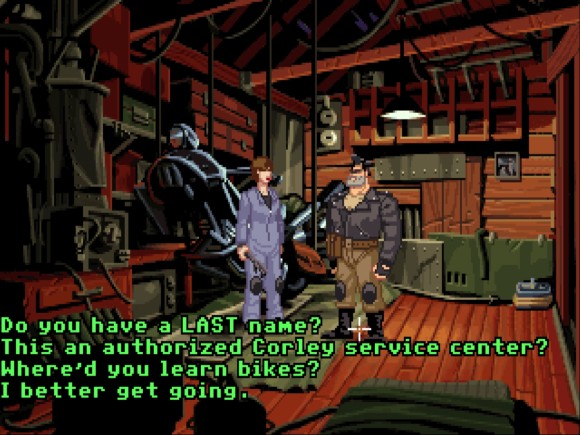

That’s not to say that Full Throttle goes full FMV adventure, rather that it sits halfway between the two genres — it’s still a LucasArts adventure game, just a massively stripped-down one. At first the differences aren’t even all that apparent, since it’s the first chapter of the game that has the most LucasArts-y elements: namely, picking up items in multiple locations and using them to solve puzzles in different locations that are reached via an area map. Even here, though, I was struck by the comparative simplicity of the puzzle design; there are five locations (Mo’s garage, the trailer, the fuel tower, the junkyard entrance and the junkyard itself) and each of them has at most a single puzzle to solve. You’ll never be carrying around more than four items in your inventory at once, either, so the solutions are usually incredibly obvious; on the one hand I did actually appreciate this simplicity for cutting down drastically on the use-everything-on-everything approach that has plagued the last few LucasArts adventure titles. On the other it does mean that Full Throttle needs to rely on its customised set-piece puzzles — the junkyard crane, the Road Rash fights, the demolition derby and so on — being ridiculously obtuse to pad out its running time, since without them it’d be about ninety minutes long.

This truncated running time is perhaps the number one reason why I’d totally forgotten playing Full Throttle all those years ago; it’s not around for long enough for any of it to really make an impression. Yes, LucasArts adventure games are all quite short if you know the solutions or use a walkthrough, but I did neither here and I was still done with the game in a little over three hours, most of which was spent smashing my head against the aforementioned set-piece puzzles, none of which land properly today. The junkyard dog puzzle was the most frustrating one, where you have to throw some meat inside one of the car wrecks to lure the dog inside and then lift the car up off the ground with a crane so that you can reach the junk pile it’s guarding; by prior LucasArts standards this is an incredibly logical puzzle solution, but the mechanical implementation of it is so fiddly that I was convinced I was doing something wrong since the crane just would not attach to the car with the dog in it. Then there’s the demolition derby, which is one of the most awful puzzles I’ve seen to date in a LucasArts adventure where you have to figure out the solution via pure trial and error, that just so happens to be masquerading as a top-down arcade driving section. There’s even a timed puzzle at the end where – gasp! – you can actually die in a LucasArts adventure game2! And the window of time in which you have to react is not large, although thankfully the checkpointing is also quite generous.

But these are sideshows compared to the main event, the thing that it feels like much of the traditional puzzle gameplay was stripped out of Full Throttle to make room for: the on-rails bike segments. These comprise almost a full chapter of the game and are part navigation puzzle, part Road Rash-style biker fights, and leverage tech that has been spliced in from the INSANE engine running the similarly on-rails Rebel Assault games in order to make it happen. This is a large part of why Full Throttle reminds me so much of an FMV game, because that’s literally what a core part of the game engine was designed to do. Fortunately for Full Throttle these segments have aged just a little better than Rebel Assault itself has (which was already looking rather rancid just a few years after release), and these days come off as more of an inoffensive gimmick than anything else. Or at least the navigation bits do; this is a game about bikers and bikes and it would be a bit weird if there wasn’t a bit of the game where you got to ride your bike around some location, even if the location in question happens to be an endless stretch of featureless brown desert backgrounds and what little gameplay there is consists of picking the right turnoff to get to where you want to go.

I’m far less sanguine about the biker fights, however — I keep comparing these to Road Rash because visually they’re very similar, with your bike going side-by-side with an enemy and the two combatants flailing at each other with a variety of weapons, but under the hood it’s actually just a heavily-obfuscated version of the Insult Sword Fighting from from Monkey Island. Each biker uses a specific weapon, each weapon has a specific counter-weapon, and defeating a biker lets you pick up their weapon. The goal is to work your way through the bikers and the weapons in a specific order until you have the one that lets you beat up the guy with the turbocharger on his engine so that you can steal it, but unlike Insult Sword Fighting (and remember, that’s the one part of Monkey Island that I absolutely despised) there are no obvious tells to let you know which weapon you should be using, and so once again you have to figure it out by trial-and-error. And after nine of these sodding games my opinion on the trial-and-error approach to adventure game puzzles should be well-known by now. I know that it was far more palatable to players back in the ‘90s, but today I can’t see Full Throttle’s overreliance on it as anything other than some desperate padding to try and make these on-rails segments last long enough to justify their inclusion in the game.

The FMV-like side to Full Throttle misfires badly, then, while the more classic LucasArts puzzle elements that are present are so simple that they pose almost no challenge to somebody who has just spent three months chewing through their entire back catalogue to date. The plot is also very thin, revolving around the main character being framed for murder by an evil motorcycle executive, whose master plan is to… stop making motorbikes and start making minivans? The stakes couldn’t be any lower if they tried, and while Full Throttle does have a wry sense of humour that I appreciated it’s not going for laughs as its number one goal either, making the story a bit of a bust too. However, despite this my opinion of Full Throttle is basically unchanged; I think it’s an incredibly forgettable adventure game, but I don’t have the same visceral, deep-seated hatred of it that I do for something like Fate Of Atlantis or Sam & Max, and that’s because Full Throttle is a much nicer game to actually play.

I don’t just mean that it’s nice to look at and listen to, either, although it is; Full Throttle is rather overfond of the colour brown but as ever for LucasArts the art and animation is absolutely top-notch and has aged exceedingly well — far better than the primitive CGI models that have been spliced into some of the cutscenes, anyway. The voice cast is superb, bolstered considerably by the (at the time) surprising inclusion of Mark Hamill at a time when he was just on the cusp of packing in his film career in favour of becoming one of the most accomplished voice actors in the industry instead. The really good parts of Full Throttle are the interface improvements, however, which walk back some of the dumber ideas we saw in Sam & Max (conversations are handled via a text interface again, which is a huge relief) along with making a couple of massive UI innovations that are still used in adventure games today.

The first is a seemingly little thing, but it produces such a huge quality of life boost that I can’t believe I played through eight games where it didn’t exist: double-clicking on a scene exit to instantly transition to the next area without having to waste entire minutes of your life watching your character slowly walk over there first. Being able to zip around from area to area basically as fast as you can think of it removes an incredible amount of downtime from the game, and is in fact a big part of why I was done with Full Throttle in just three hours. Indeed, the cynical part of me suspects this might be why they didn’t include this feature in Sam & Max when it was so sorely needed, although it’s also possible that this is an actual tangible benefit of the switch to CD-ROM. Whatever the reason, this feature is the number one factor behind the last three 2D LucasArts adventures — Full Throttle, The Dig and Curse Of Monkey Island — feeling so much more modern than their predecessors, and it’s why Full Throttle gets away with a lot despite being the weakest of the three.

Then you have the new action verb interface. Full Throttle quite rightly looks at the awkward, overly-clicky way Sam & Max handled verb selection and tosses it directly into the garbage. But it doesn’t give up by going back to the space-inefficient verb menu at the bottom of the screen either; instead of either of these approaches, Full Throttle pioneers the now-standard right-click verb menu. If you see something interesting in a scene, mousing over it and clicking once with the right mouse button brings up a heavy metal album-style cartoon skull with a fist and a boot sticking out of the sides of it. Mousing over various parts of the skull bring up appropriate verbs you can use to interact with the object in question — eyes for LOOK, mouth for TALK, fist for PICK UP and so on — and clicking on a verb instantly executes that action on the object. This solves nearly all of the problems the previous two interfaces had: the entirety of the screen can be used for art and animation, you can still see most of the screen when you have the verb menu open since it’s a much more compact interface, and it’s still only two mouse clicks to do something. Full Throttle doesn’t get it 100% right the first time since the inventory still blocks most of the screen when you open it, and they also made the mistake of relegating tooltips to the right-click menu meaning that when you find an interactable object you have to open that menu just to find out what it is, but I also think that Curse owes a lot to being able to refine this interface instead of inventing it whole-cloth, not to mention a lot of modern adventure games — including the two Monkey Island remasters — also using an improved version of it. And it says a lot when the control system you invent for your game is still the genre standard twenty-five years later.

It’s thanks largely to these improvements that, for the very first time in this series, my frustration with Full Throttle was directed almost exclusively at the puzzles rather than the actual mechanical process of playing the game. When Full Throttle has to come up with a specialised gameplay system for a specific puzzle, as with the junkyard crane or the demolition derby, it often falls flat on its face and I really wish it hadn’t relied on them quite so heavily. Outside of these segments, though, Full Throttle feels about as natural to play as an adventure game can be, even if it does end up being a bit too simplistic and, ultimately, disposable; I might have disagreed significantly with some of (in fact a lot of) the puzzle design, but at least I didn’t resent the game for making my life unnecessarily difficult. Doubtless I will have forgotten all about Full Throttle in a year or two (again) and I’ll almost certainly never replay it, but it didn’t leave quite such a bad aftertaste as certain other LucasArts adventure games I could name, and that alone is enough to raise Full Throttle up above the majority of its peers.

>I am incredibly disinterested in bikes, bikers, heavy metal

This is a rare moment when I’m surprised by your poor judgement!

Heavy metal aesthetics is often used in video games, you can’t imagine Doom, Devil May Cry or Metal Gear Rising Revengance without it. But Tim Schafer made 2 games that are not just influenced by metal, they are about metal. One is adventure game and the other is RTS, kinda. With RTS you can at least imagine something metal about leading your legions to victory (still, microcontrol and resource management are not metal), but adventure game?.. Using 3 liter and 5 liter buckets to get 4 liters of water is the least metal thing ever. Yeah, the game is all ironic about its subject matter but it should have been an episode of a bigger game. It feels similar to what you’ve thought about Sam & Max: someone on the team really wanted to make a game about this subject. But they could only make adventure game so here you are.

Wonder why it’s well remembered. Even earned a remaster.

Well, maybe I shouldn’t have included heavy metal in the list. It has its place, especially in the Revengeance soundtrack, which I referred to at the time as something you wouldn’t want to listen to on its own but which subsequently made its way into several of my running playlists. I stand by the biker/bikes comment though.