So I guess I got what I wanted out of this project. Despite having played through The Secret Of Monkey Island six or seven times over the past three decades, and despite already thinking of it as a stone cold classic, experiencing the trials and travails of LucasArts prior to its release gave me a whole new appreciation of why it’s a classic. It’s an adjunct to my Bad Game Theory, where you need to play the occasional bad game to give you the right context for what a good one looks like; here I needed a better appreciation of the games that had come before it to fully understand why Monkey Island was such a groundbreaking tour de force of art, humour and puzzle design.

(Another word on versions. Monkey Island’s original release was the EGA version, which I have been playing for this series. A couple of years later it received a VGA rerelease just like Lucasarts’ other titles. This version is acceptable and is the one I previously played through, although I think the more I do this the more I’m becoming an adventure game purist who thinks they must be enjoyed in the Original Format Only to avoid losing anything in translation; the VGA art for Monkey Island is more detailed but also flatter and less punchy, and I think I like the EGA art better in 90% of cases. Then there’s the 2009 Special Edition, which I regard as nothing short of a complete butcher’s job; modernising the interface and making it fully voiced means it loses a lot of the visual humour and text-based joke timing that defined Monkey Island, while the new art is not particularly attractive and is also locked to the same animation frames as the old art, which only serves to draw attention to how jerky and stilted it is. Its sole redeeming feature is that it includes the VGA version as its obligatory Classic Mode, and that’s the one you should play if you buy it.)

The Secret Of Monkey Island needs little introduction today, but I do chuckle when picturing somebody picking up the box for the first time back in 1990. The box art on its own is a classic, an excellent fusion of the Drew Struzan movie poster style with Steve Purcell’s art, and which promises a pirate-themed adventure with swordfighting, treasure-hunting, romance, undead ghost pirates, eyeball necklaces and gigantic stone monkey heads. It’s even one of the most technically accurate pieces of box art ever produced, since everything that is on the box is in the game in one form or another. It also drastically mis-sells the game’s tone, however, and I can easily imagine this hypothetical first-time purchaser being outraged to discover that this is not a pirate-themed adventure game, but a pirate-themed comedy adventure game, and which has a very definite opinion on which of the three elements is most important (hint: it’s not the pirates or the adventure). All of the previous LucasArts adventure games have tried to be funny but mostly misfired1 Monkey Island is the first one to go in this heavily on the comedy and genuinely succeed — there’s no deliberate anachronism that Monkey Island won’t insert in the name of a good joke, no fourth wall it won’t break in order to lampoon both itself and the wider adventure game genre — and now that I’ve actually played through the previous attempts I have to say I think this would not have been possible without them. You can’t make a game like Monkey Island until you can make a game like Monkey Island; you need artists and animators who have built up the skills needed to make the visual gags work, you need somebody to look at the conversation system in Last Crusade and think “Hang on, we could do a lot more with this…”, and you need players to be familiar enough with the general concept of point and click adventure games for Monkey Island’s meta humour to land properly.

Let’s start with what’s become the meat and potatoes of these retrospectives: the art and the interface. Prior to this runthrough I had only played the VGA version of Monkey Island and I thought the EGA version was… not ugly as such, but certainly very basic, and only something you’d put up with if you had an ancient computer that couldn’t do VGA; 256 colours are clearly better than 16 colours, after all. Having seen how the visuals have improved from game to game as Lucasarts have tried new things with each one, though, I have a new appreciation for Monkey Island’s EGA artwork. Steve Purcell and Mark Ebert continue the solid work they turned in for Last Crusade and are joined here by Loom’s Mark Ferrari, and together they push the pixel dithering technique about as far as it can go. For example, here is the first thing you see after starting the game and talking to the lookout:

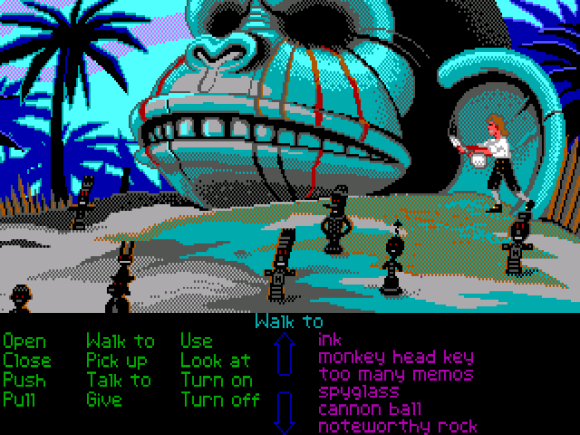

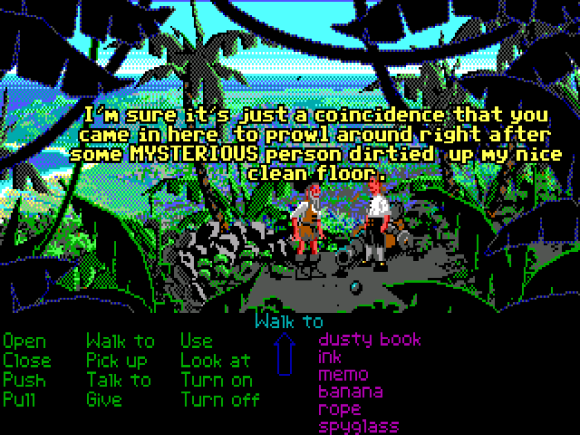

That is one hell of a statement; this actually beats the VGA version’s rendition of the same scene, which drops the sunset and looks a lot flatter. If you have any appreciation of retro pixel art, Monkey Island is nothing short of incredible. The first half of the game takes place on a perpetually night-shrouded Melee Island, which lets the artists use those blues they liked so much in Loom to great effect; the island is essentially a collection of silhouettes with the edges and detail picked out in blue (to denote starlight) and the occasional flash of yellow and brown when there’s an actual light source present. It’s an effect that I like very much; I did always wonder why Melee used such a curious colour scheme when I was playing the VGA version, but now I completely understand. Interior locations can be a little basic, but the exteriors are all gorgeous, which is not a word I was expecting to use about EGA art when I started this series — Monkey Island has the same resolution and colour palette as Maniac Mansion, but looks a million times better. What’s particularly impressive about Monkey Island, though, is that when the story shifts to the daytime jungle environment of Monkey Island itself — and “daytime jungle” is not something that LucasArts have historically handled well up until this point — the art is still pretty solid. They have to make some odd colour choices, like the giant stone monkey head being picked out in grey, black and…. light blue? It’s never less than acceptable, though, and they manage some excellent background art on Monkey Island in spite of this being their weakest area.

Not only is the artwork just generally great, though, but there’s also an increased level of bespoke one-off animations when Guybrush performs a specific task. These featured in Last Crusade but there were only seven or eight of them compared to the dozens found in Monkey Island: Guybrush digs for treasure, he uses his rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle to cross a chasm, he gets fired from a cannon across a circus tent (from two different angles), he uses a giant cotton ear bud to clean the ear of the giant stone monkey head (don’t ask)… these give him a ton of character compared to the static protagonists of Loom and co., not to mention being a prime source of a lot of the visual jokes in the game. The talking-head close-ups also return whenever you talk to certain characters in the game, and while they’re used rather oddly — I get that Carla and Captain Smirk deserve close-ups, and they’re great ones, but why do these three random pirates in the SCUMM bar get them too? — they serve to add that additional bit of atmosphere to the game.

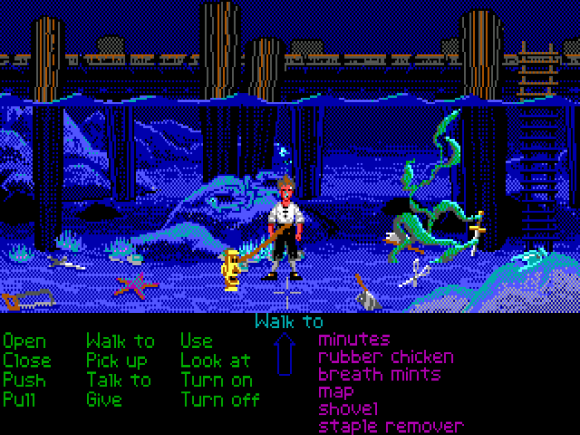

The interface makes it across from Last Crusade with all of the same basic features, but also with two very important changes. First is that the verbs and the inventory have been rearranged to sit side by side instead of on top of one another; this changes the inventory into a more logical single-column list format and lets them have six inventory items on screen instead of four. It’s a much more efficient layout, and the reason LucasArts can make this change now is that they’ve ditched several of the more redundant verbs from previous games: SWITCH is gone because there’s no character switching in Monkey Island, and there’s no incredibly specific verbs that you only use once or twice like TRAVEL or PUT ON/TAKE OFF. Most importantly, WHAT IS has finally been thrown into the garbage where it belongs; Monkey Island instead inherits the dynamic tooltip-on-mouseover behaviour that Loom pioneered (albeit in an unorthodox form) and which became the standard functionality for all LucasArts adventure games from this point forward.

These two changes make Monkey Island so much nicer to play than any of the previous games since the amount of unnecessary clicking feels much reduced, but Monkey Island has even more to offer on the usability front. LOOK now works as it should, with most things in the game having unique LOOK descriptions which sometimes hint at what Guybrush is supposed to be doing with them, and Monkey Island also has a conversation system that’s actually worthy of the name — in fact it’s the first thing the game shows you after the title screen as pirate-wannabe protagonist Guybrush Threepwood accosts the old lookout on Melee Island for information about the pirates there. Here you get your first short-term goal of talking to the pirate leaders in the SCUMM bar; doing this gives you the Three Pirate Trials to complete, along with a feeling that they’re taking you for a ride, but you also get hints on what you need to do next — you’re explicitly told you need to go and visit a sword trainer before you can beat the Sword Master, the pirate leaders suggest drugging the dogs guarding the Governor’s mansion, and one of the pirates also gives you the idea of sneaking into the kitchen while the cook’s back is turned. Going to the sword trainer without a sword just results in him telling you you need to get a sword first. Okay, where would I get a sword? Does the store in town have one? It does, but I need 100 pieces of eight. Those weird guys I met at the circus promised to pay me much more than that if I let them fire me out of a cannon, but I need something to use as a helmet. Hmmm, perhaps this pot I stole from the kitchen will work? Relating all of this information to the player via the conversation system gives them a hell of a lot more to work with when trying to solve the game’s many puzzles, most of which would probably be quite obtuse if they weren’t so heavily signposted. This sense of direction is something that was completely lacking from the previous LucasArts games that I’ve played; it’s been eleven years since I last played it and I’d forgotten more of the game than I would like, but Monkey Island is still only the second game in this series that I didn’t need a walkthrough to complete.

And obviously thanks to the conversation system making everyone in Monkey Island an order of magnitude more chatty, it’s also a primary channel of expression for the game’s abundant sense of humour. Monkey Island is inspired by a range of source material that includes pirate theme park rides, and so its world is a tacky, artificial version of pirate havens and jungle islands, where you come away from your hunt for buried treasure with a souvenir T-shirt and the Monkey Island cannibals spend all their time sniping with the undead pirates over who has the access rights to the giant monkey head. It’s absolutely full of absurd anachronisms and throwaway jokes that would be lazy and one-note if they weren’t so well-handled. Take Stan, for example. The idea of a used-boat salesman on its own is enough to elicit a brief chuckle, but it’s also the sort of thing that a lesser game would assume would be enough to stand on its own. However, Stan is such an exquisitely-written parody of a salesman that the joke has legs that take it far past the point where it should have gotten old (i.e. roughly two seconds after meeting Stan), and even so Monkey Island has the good sense not to let it outstay its welcome; Stan shows up to do his salesman routine, sticks around for one medium-sized puzzle (that he helpfully points you towards), makes a brief cameo at the end and then disappears until the next game — and he’s used pretty sparingly there too. Unlike a lot of modern games Monkey Island knows not to overdo its humour, and so while there is a lot of it, it’s always hitting you with a new joke instead of parroting the same tired catchphrases in the sadly misguided belief that repeating the Funny Words is, in and of itself, funny. Some of them don’t land, but that’s okay, because most of them do — and anyway, there’ll be another three along in a minute.

(It’s also smart enough to make its deliberate anachronisms timeless things in and of themselves. Monkey Island doesn’t reference specificities with its anachronisms, but generalities — concepts like tacky tourist traps, theme parks, health fanatics and overly-complicated legalese. The closest it gets to a specific parody of a real-world thing is the Grog machine that’s a clear piss-take of Coca-Cola, which still works because Coca-Cola isn’t going away any time soon. Because it’s not referencing specific elements of pop culture the humour has aged far better than most of its contemporaries, and in fact better than its own sequel.)

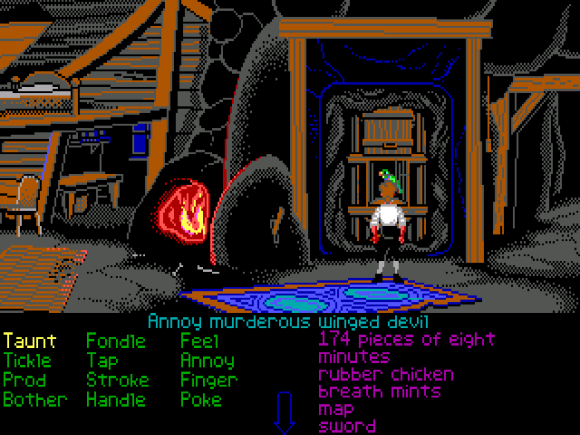

What I find most impressive about Monkey Island’s humour, though, is the way it tells some of its jokes by subverting the game’s interface. Take the cannon incident I mentioned earlier: Guybrush is fired out of a cannon, strikes a pole in the middle of the circus tent, and lands upside down on his head. The Fettucini Brothers rush over to check that he’s okay, and the conversation system pops up two possible responses — but they’re written upside down too. That’s a really nice piece of subtle humour that leverages the player knowing what the game’s interface should look like by now, and so Monkey Island can start playing around with it. Your encounter with the winged Terror of Hook Island temporarily replaces your entire set of action verbs with synonyms for “annoy”. The fight with the sheriff in the governor’s mansion takes place almost entirely offscreen and is punctuated by sound effects and the occasional comic book-style POW!, but what’s actually happening in the fight is related to you via the game taking control of your command bar and constructing increasingly absurd commands using unseen items, like USE STAPLE REMOVER ON TREMENDOUS DANGEROUS-LOOKING YAK. I even got to experience Monkey Island’s infamous Stump Joke for the first time here: Guybrush finds an innocuous-looking tree stump in the forest, and examining it with LOOK reveals a whole network of caverns and catacombs underneath it! Attempting to climb through to the catacombs prompts you to insert Disk 22, then Disk 36, then Disk 144, and when you don’t insert any of these Guybrush sadly comments that he won’t be able to access that part of the game2. This absurd interface humour is the part of Monkey Island that I like the most, and I think it’s the part that really wouldn’t work without a solid history of LucasArts adventure games to draw on, since you can’t both create something new and subvert it in the same game.

Really, I was very pleasantly surprised at how well Monkey Island holds up today. The one area that hasn’t aged tremendously well is the music; Michael Land’s themes for the game are classics but he doesn’t have the technology (or the disk space) to fully realise them in this original EGA release and so they end up falling foul of the very basic sound technology available on a 1990-era PC. It’s not bad, as such, and does a perfectly good job of keeping the ears occupied while the brain works, but the various tracks do sound like warped versions of much better music. (He fixed this a few years later with the CD rerelease though.) Also I have a deep personal dislike of the insult swordfighting mechanic, although that’s probably just because it’s the one part of the game that has been absolutely run into the ground over the subsequent decades. Otherwise Monkey Island barely lost a step despite being thirty years old; it’s a perfect coming-together of humour, art, puzzle design and writing, and it strikes an excellent balance between the four that I feel they really struggled to recapture on subsequent attempts. There are other games from the same time period that are talked up as classics but which are all but unplayable today, but The Secret Of Monkey Island wears its classic status better than almost anything else I can think of, and so I think it’s one of those very rare games that actually deserves it.

- Except Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade, which got away with it by not shoving its humour in your face and restricting itself to wry jokes and visual gags. ↩

- The reason I’ve never seen it before is because LucasArts got a lot of angry phone calls from players asking where Disk 22 was, and so the joke was removed in all subsequent versions of the game. ↩

The remake indeed sucked, but the voicework was actually very good. The problem was that they messed up the delivery of the lines i.e. it was a programming error rather than a bad recording. The best version of Monkey Island 1 is therefore the Ultimate Talkie edition you can make in ScummVM using the music and lines from the remake. See http://www.gratissaugen.de/ultimatetalkies/.

I first encountered Monkey Island via The Curse of Monkey Island, which significantly affected my perception of the series, but honestly, all of the games in the franchise are pretty decent despite being made by multiple different teams across two different companies. Kind of unusual, really.

Ok,

you convinced me to go play it (VGA mode). So far it’s indeed funny and not too obtuse. Thanks!

I think Monkey Island could be so confident in its genre parodies because they weren’t just parodying the fairly nascent point’n'click genre, but also the older text adventures that relied on certain patterns of commands, and often used the same flavour of “game logic” such as obtuse puzzle solutions, improbable carrying capacity, etc. Not to say that MI doesn’t pull it off astonishingly well by any standards, but I remember feeling like it was joking about “adventure” games in general

i hate this game i cant do kamwehamaehan and thereds no fortnite