Indiana Jones And The Fate Of Atlantis is second on the list of games I was most looking forward to playing for the first time as part of this series. Unlike most of the other games on that list it’s only ever referred to as a stone-cold classic — both at the time and by anyone you ask about it today — and I also quite liked Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade despite that game being comparatively clunky and obtuse by modern standards. The concept of an Indiana Jones adventure game clearly has legs, and I was excited to play something wholly original that wasn’t shackled to a movie script, and which had been developed during LucasArts’ true golden age.

Imagine my surprise, then, to discover that, contrary to everything I’d heard about it over the last quarter-century, Indiana Jones And The Fate Of Atlantis fucking sucks.

Oh, it’s not without a few interesting ideas that expand on the multiple-routes idea pioneered by Last Crusade, but make no mistake: Fate Of Atlantis is a terrible adventure game which reminded me of nothing more than Zak McKracken in a fresher coat of paint. It has the same depressing tendency to revert to Adventure Game Logic when solving puzzles, the same misguided belief that having the player blunder around in a pitch-black room for twenty minutes counts as interesting gameplay, and the same utterly inexplicable love of mazes. That last item is taken to the point of absurdity here, since practically the entire back half of the game is nothing more than a series of mazes with a few substandard, illogical puzzles scattered inside of them. I very nearly didn’t make it to the end of Fate Of Atlantis, even with a walkthrough, because the process of going through maze after maze after maze was slowly sapping my will to live. LucasArts had released two Monkey Island games by this point! They know better ways of making adventure games now! Hell, the team responsible for Fate is the same team responsible for Last Crusade, which did a lot of this stuff (especially mazes) in a far more bearable fashion and would have been quite easy to spin into a respectable adventure game with updated graphics and “modern” conveniences. What on earth made them think they should go backwards in time and double down on all of the genre’s most insufferable vices?

Fate Of Atlantis at least starts fairly promisingly. You get the classic Indiana Jones title card, and then a cute little introduction sequence where Indy bursts into a storeroom on a search for an ancient artifact and pratfalls his way from screen to screen while the opening credits play. But wait, what’s this?

Where is the familiar list of action verbs? Where is my inventory? The intro to Fate doesn’t have either, instead plumping for full screen backgrounds and an actual, honest-to-god tooltip that pops up next to the mouse cursor when you hover over something interesting. Clicking on the thing causes Indy to either make an observation about the thing or attempt to interact with it. I was initially very confused by this, because it appeared that Fate Of Atlantis had come up with the next big leap in adventure game interfaces a year or two early1: ditching the on-screen interface and instead implementing context-sensitive mouse controls. The reason I was confused is because I had at least seen screenshots of Fate in gaming magazines at the time, and I definitely remembered it having some kind of interface, and I briefly wondered whether or not I was playing some later rerelease that overhauled it out of the game.

I needn’t have worried, though; there is only one version of Fate Of Atlantis, and it’s the one composed of pure 100% certified A-grade shit. (They did add some incredibly bad voice acting in the now-obligatory CD rerelease a year later, but I turned it off within ten minutes of starting the game and the versions are otherwise identical.) A more traditional adventure game interface appears the moment the opening credits are done, and it is spectacularly ugly with none of the charm of Monkey Island 2’s take on the concept; I know that it was the style at the time for most computer-related things to be beige, but there’s no reason Fate’s inventory and buttons have to be as well. The intro scenes themselves are strikingly lit, leveraging some of what was learned over the last three years, but subsequent locations are… not badly drawn, as such, they’re just a bit generic in style; unlike Monkey Island 2, Fate’s backgrounds are obviously art for a videogame, rather than art that has been transplanted into a videogame. If you slapped a background from Fate Of Atlantis next to a background from (to pick a random contemporary example) Shadow Of The Comet, I think I’d struggle to tell you which one was which. After playing Last Crusade it was nice to control an Indy who wasn’t composed of flat colour blocks and had a bit more detail to him, but at the same time that detail is somehow indistinct — there’s a lot of light and shade applied to a generally Indy-shaped silhouette, but not much in the way of recognisable features.

And that’s the problem with the art in general: it might never look less than okay, but it has a serious readability issue when trying to pick out actually important detail from the background art. I could mouse over a scene once, twice, three times and not actually find the important item that’s present because it’s blending in so well with the background scenery. This is a running thread throughout the entire game, starting from the library at Barnett College, running through Tikal and Algiers, Crete, and then finally into Atlantis itself; in all of these locations I missed critical items not because I hadn’t spent enough time inspecting the location — this is the seventh LucasArts adventure game I’ve played so far and I’ve gotten quite good at it — but because it was so hard to see them against the fuzzy backgrounds. It doesn’t help that Fate Of Atlantis has also inherited Last Crusade’s obsession with pixel hunting; here at least the objects you’re hunting for are three pixels big instead of one, but when you make them that small it’s no wonder they get missed even by a reasonably on-the-ball player such as myself.

Puzzle-wise Fate Of Atlantis does try something interesting. A common criticism of adventure games around this time was that they had zero replayability: you’d play the game once, and then there’d be no point playing it again because you knew the solution now and it’d play out the same way every time. This is why so many of the early LucasArts games contain features such as character switching and randomised puzzle elements, and it’s why Last Crusade also tried out the idea of alternate routes through the game — steal the biplane or board the zeppelin, fight the big guard or get him drunk, and so on. The idea was that the game would track your score across multiple playthroughs, and only by exploring every possible path would you be able to achieve maximum points. Fate Of Atlantis does the same thing, but in a much more structured way; the game’s plot is a fairly standard race against time to discover Atlantis before the Nazis do (if I were feeling particularly uncharitable I’d call it a straight rip-off of Raiders Of The Lost Ark), and Indy hooks up with a bogus psychic called Sophia Hapgood who has a connection to Atlantis. Sophia follows Indy around during the early part of the game; she isn’t a directly controllable character but can be talked to in order to get hints on where to go next or to create distractions. After the first few locations are out of the way she gives Indy a choice under the guise of telling his fortune.

- Ditch Sophia in New York and continue solo, with an emphasis on puzzles.

- Ditch Sophia in New York and continue solo, with an emphasis on the returning boxing minigame.

- Let Sophia accompany you and continue to use teamwork to solve puzzles.

Each option changes how the middle portion of the game progresses; Indy will visit Monte Carlo, Algiers and Crete regardless, but the specifics of how each location plays out depends on which path he took, where he reaches the Algiers dig site on a camel if you choose the Wits path, but has to steal a balloon instead if you choose Teamwork. The puzzles solved with Sophia present are quite significantly different than those solved without her, and if you choose Fists you always have the option of punching Nazis in lieu of solving the harder ones. The Indy Quotient scoring system also returns, and only by playing all three paths can you max out your score.

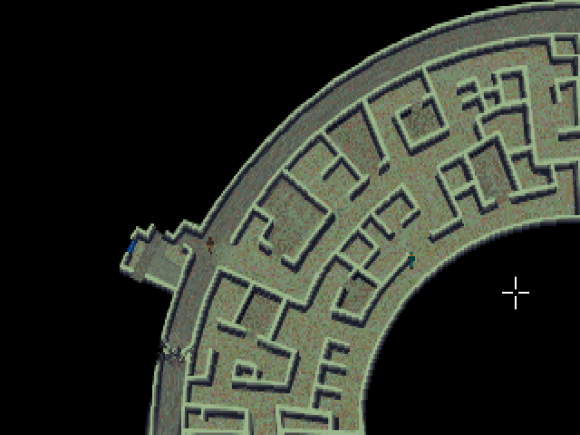

On the face of it this is all quite welcome, but it’s a plan with one tiny flaw: the end of each route, in Atlantis, is exactly the same (Sophia gets kidnapped by the Nazis and transported there if you didn’t bring her with you), and this is by far the most tedious part of the game. The first segment of Atlantis is a big, top-down circular maze split into four chunks, with each chunk having 4-5 rooms in it. The locations of the rooms are randomised on each playthrough, and you have to visit them in a specific order — you need an insulated cup from the statue room so that you can fill it with lava in the lava room so that you can pour the lava into the machine in the machine room — which means at least two trips around the maze, one to find out where everything is and another to actually do the things you need to do. Then there’s some incredibly awful backtracking, where you need to bring a collection of items from the maze through five screens’ worth of canals (hope you didn’t miss any of them!) so that you can use them to break down a door into the inner section of Atlantis. This also knocks a hinge pin loose, and if you want to save Sophia you have to go back out through the canals and into the dungeon so that you can use the hinge pin to free her. A big thing Fate Of Atlantis likes to do is repeatedly use the same item over and over again to bypass an obstacle, but with no hints given that you’re supposed to pick the item up again after the first time you’ve used it; after you’ve freed Sophia the hinge pin is stuck in place propping up a door, so I left it behind and went forward again through those five screens’ worth of canals plus another three screens’ worth of corridors only to discover that I needed to insert a lever-like object into an ancient digging machine, a lever-like object much like… that hinge pin. So back I went for it through eight screens’ worth of wasted time and then again on the return trip, where Monkey Island would have just had your character automatically pick the hinge pin up when I tried to leave the room for the first time and saved me from all of this tedious backtracking.

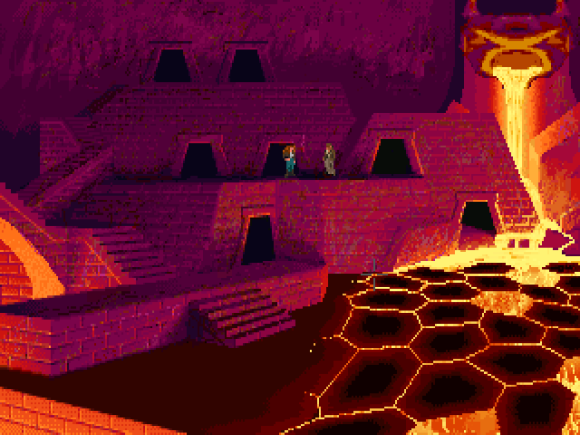

Finally, once you’re through the maze and the canals and the backtracking and you’ve turned on the digging machine, it bursts through a series of walls to reveal… another maze, this one of the screens-with-multiple-connected-exits variety. I had to quit the game for a few hours at this point, despite knowing that I was very close to the end of the game, because I couldn’t bear the thought of going through the third successive maze. Fate Of Atlantis had several of these moments; one thing it likes to do is throw Indy into a dark room and make him blunder around in the dark trying to find the light switch. On the plus side these scenes have significantly more effort put into them than Zak McKracken did, as Indy’s eyes slowly adjust to the dark over time and he can start to make out the general shape of objects so that he can interact with them. Objects in the room don’t have specific names while it’s dark because Indy can’t see what they are; they’re just referred to as “wood thing” and “stone thing”, and he has to get up close and touch them before he gets a detailed description. However, what makes them so much worse than Zak McKracken is that turning on the light is no longer a process of finding the light switch and turning it on, but is instead a multi-step process of refueling a generator with fuel siphoned from the truck outside, or putting down a ladder so that you can reach a statue that you have to insert a magic bead into, and having to do all of this in the dark is incredibly obnoxious as it involves several separate stages of sweeping the room with the mouse cursor to try and find the interactable objects (as if I weren’t doing that enough in this game already) and then figuring out what order to use them in.

And then there’s some examples of Adventure Game Logic in here that I can only describe as spectacular. Early on Indy is faced with a coal chute that he cannot climb up because it’s too slippery. His solution to this problem is what any of us would do when faced with the same situation: get some chewing gum that was stuck to one of the desks upstairs and stick it to his shoes to provide traction, as it’s well-known that the adhesive strength of chewing gum is more than enough to support the weight of a full-grown man. Shortly afterwards, in Tikal, Indy picks up a kerosene lamp and takes it inside a pyramid. Now, if you or I were to put a kerosene lamp into an adventure game, it would probably be for the purposes of “making light”, or possibly “making fire” as a secondary option. Fate Of Atlantis instead elects to use the kerosene inside the kerosene lamp as a solvent to clear away the dirt around some of the engravings in the pyramid, because that’s obviously the first thing that comes into everyone’s heads when they think of a kerosene lamp. Indy has to dig holes at several points in the game, and the thing he uses to do it isn’t a shovel, but an ancient ship rib (i.e. a stick) that he finds on a table in Algiers. In Atlantis he has to distract an octopus before he can traverse the canals, so he has to go back into the maze, pick up a specific human ribcage — there are bones everywhere in Atlantis, but only this ribcage will do — combine it with a sandwich he picked up on a Nazi U-boat, and then chuck the whole thing into a pool full of crabs. This is apparently a foolproof method of catching one, which he can then use to placate the octopus.

God, just reading some of the solutions in the walkthrough made me angry. (And yes, I resorted to a walkthrough halfway through Crete because I couldn’t stand the game’s magical thinking any more; looking back on it I’m amazed I made it that far before cracking.) Indiana Jones And The Fate Of Atlantis might have multiple routes through the game, but after being bored to tears by the Teamwork route I was in absolutely no mood to try either of the others; the boxing minigame is much harder this time around, and you absolutely cannot convince me the absurd puzzles would be improved by making them more complex on the Wits path — and anyway, they both terminate in the same tedious trek around the Atlantis mazes. After hearing so much about the game’s quality — both in contemporary gaming media and by starry-eyed fans for decades afterwards — and after how promising Last Crusade turned out to be, it’s dreadfully disappointing that Fate Of Atlantis has seemingly learned nothing from LucasArts’ subsequent efforts and ends up feeling like nothing more than a deliberate throwback to the Bad Old Days, and a good reminder of how far adventure games have come since then.

- I think the first game to properly do away with the on-screen verbs was Sam & Max in 1993, although I’ve not played it so I can’t be sure. Full Throttle definitely did in 1995. ↩

While my school playground generally considered this to be a great game, I think because it held up enough of the film tropes in our mind to be the hidden 4th film that we were privileged enough to access through our A500+s, even as children we knew the “3 paths” were bullshit. The fighting path was completely dull, and the fact that Sophia is always there at the end made it obvious even to pre-teens that the team path was the “true” path even if the solo wits path had a few different puzzles along the way

Thanks for suffering for the sake of history of the art.

It’s fascinating how adventure games have risen up from hostile depths of interactive fiction verb-guessing games, journeyed through huge mainstream success and then destroyed themselves with magical thinking puzzles. I know it’s a long time between Fate of Atlantis and genre death, but it’s hard to decipher whether those issues are because of the genre legacy or is it a glimpse of the future.

The main difference is that adventure games are virtually unlimited design-wise — they’re not system-based.

In action games, you have a few verbs (shoot, move, jump) and you explore a story around those verbs, one which gradually requires more skills or throws in the occasional new verb.

The same can be done with puzzle games — generally you only have a few verbs. You start building up the player’s vocabulary, exploring variations with those verbs as you go.

Adventure games don’t build up. The puzzle you solve in the first minute of the game generally has nothing to do with one you’ll solve 30 minutes in. The verbs are all your regular verbs (use, look etc) but also all your inventory items, and the ways they affect the environment vary widely from scene to scene, depending on the developer’s ideas. There is no system that you gradually learn, explore and improve at — each puzzle stands on its own. As a result, the designer must be extremely cautious in his design to lead you logically and clearly from one scene to the next. if some puzzle along the way is terrible, it can completely derail the experience.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the best games of the genre *do* adhere to a system of sorts. e.g. Day of the Tentacle and its time travel-based puzzles.

Indeed. Those traditional adventure games requiring you to apply items on items often feel like interactive movies of their time. It’s no suprise Telltale games started as a classical adventure revival project but quickly fell into being the interactive movie company.

I know Myst is appreciated for its technology first and foremost, but it was interesting in that it felt like you are solving realistic problems of operating alien magic devices instead of combining honeycomb with a screwdriver to achieve some unpredictable result. Some recent Sherlock Holmes games are interesting too: they have sort of mind map allowing you to combine evidence into deductions, and some evidence may be false or deductions may be wrong. It never feels like the system is used to its full potential but it feels like a real problem solving unlike many classic adventures as well as modern nostalgic adventure games.

Yeah Myst and Riven etc were basically admissions that the inventory puzzle system is too ridiculous for a serious game. By limiting your verbs to pushing buttons and moving levers, they reduce the scope of your expectations. Every Myst/Riven puzzle is basically one of a machine without a manual, and so every one feels logical. Even in this sub-genre though, only great developers can reach the heights of those two games. Abusive developers can waste the player’s time with buttons that seem to do nothing and activate some machine far away.

I should check out the Sherlock Holmes games. Sounds a little like the system used in the Blackwell Wadjet Eye games.

More than anything, I think that good adventure games need a built-in hint system. Most action game don’t want the player to be stuck for long, and neither should adventure games. The player should be able to refuse hints if they so choose, but in general the game could track how long the player is stuck and have characters offer more hints as needed. Together with avoiding ‘dead man walking’ syndrome, this would remove the frustration element. Of course, ideally the puzzles would be designed in a way that directs the player towards the solution, but an organic hint system would help with those times when the designer fails.

Sherlock Holmes are somewhat similar to Blackwell games, yes. More casual, I’d say, and they still have some simple traditional puzzles. Crimes & Punishments and The Devil’s Daughter are the good ones, earlier games are just your regular adventure games with a lot of subpar writing.

It’s funny I didn’t remember it being this bad. I think it’s still *so* much better than what Sierra was producing at the time that I didn’t notice the issues so much. Perhaps it’s an issue of mentality: if you go in expecting cartoon logic and silly puzzles here and there, it appears better. To me it was also far, far better than the Last Crusade, and fairly enjoyable on the whole. I’m not sure what made you expect realistic solutions to inventory puzzles – very few adventure games do that, and it would generally just be pretty boring. In real life one doesn’t carry or use too many objects in creative ways. If action games can have us kill thousands of mindless enemies with unrealistic odds, is it really so bad that adventure games have us be flexible with object usage? Can our suspension of belief really not tolerate such a thing?

Also, I’m surprised you didn’t comment on the change in the *type* of puzzles. There are far fewer inventory puzzles, several dialog puzzles, and many more ‘how do you make this device work without a manual’ puzzles of the Myst variety. I also enjoyed the reuse of items — the limited inventory made it seem more realistic (relative to these kinds of games). I even liked the little action bits, as weak as they were on the Scumm engine.

Finally, I believe numpad 0 gives you an insta-win on almost all fights.

You are just wrong. But that’s ok.

I don’t think you were supposed to be able to win that particular fight in The Last Crusade without getting the guard drunk. There’s a youtube video “Indy beats sober Biff”, which says it took thousands of tries to manage it, and the fight pattern it uses looks very unnatural.

Hm. I’ve played Indiana Jones and The Fate Of Atlantis when it was brand new (yes, three decades ago). It still has a very special place in my heart and gaming memories, and even today I still think it’s the best Indiana Jones story and game. I also still firmly believe that The Fate of Atlantis is what the fourth Indiana Jones movie should have been instead of the crap that they eventually decided to give us instead. In comparison, Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade – both the game AND the movie, however, actually DID suck completely and I couldn’t play The Last Crusade for more than two hours because I found it so horrible. Indy IV, however, was interesting enough to play a few more hours after having finished it to see some of the alternate endings.