Project Wingman is an interesting one. It’s an indie take on the arcade-style fighter jet shenanigans of the Ace Combat series that’s been made by a tiny team with a fraction of the budget that a full Ace Combat game would get, but which is attractive to me for precisely that reason. I have never played an Ace Combat game, mostly because the trailers all tend to feature a rather larger quantity of pre-rendered cutscenes and interminable voiceovers than I’m really comfortable with in what’s supposedly an arcade shooter. I bought Project Wingman in the hope that an indie approach to it would cut all of that extraneous stuff out (because it doesn’t have the budget for it) and instead focus all of its resources on the part of Ace Combat that I’m actually interested in: re-enacting Top Gun with a console controller.

My initial impressions of the game were not positive. Project Wingman is billed as being made by Ace Combat fans for Ace Combat fans, which I suppose is very nice for the Ace Combat fans but not so much for someone like me who has no experience of the series, because it makes certain assumptions about how the game should play with a controller that are completely at odds with how I usually play games with a controller. Turning was locked to the trigger buttons1 while the right thumbstick was relegated to a collection of static camera padlocks and firing my weapons required me to hit face buttons, which is just all backwards — they are triggers, they should be used for firing guns. Yes, I understand that if I were using a more flight-simmy HOTAS setup I’d just be thumbing a button on top of the joystick to fire a missile instead, and I’m not disputing that this default controller layout probably does make a lot of sense to somebody who has played a lot of Ace Combat games. For me, however, it was deeply alien, and it wasn’t at all helped by the tutorial level not having any of the dynamic button tooltips I’m used to in modern games — you know how normally if it was teaching you how to switch targets it would say “Press Y (the controller face button) to switch target!” if you were using a controller or “Press T (the keyboard button) to switch target!” if you were using a mouse and keyboard? Project Wingman isn’t smart enough to change things up based on which method of control input you’re using, and instead thinks “Press the Switch Target button to switch target!” is a helpful thing to tell the player instead of one of the most useless pieces of tutorialising I have ever seen.

So I figured that since I was going to have to delve into the key bindings menu anyway to figure out what the Switch Target button actually was, I might as well try and rebind things into a control setup that my aging brain could cope with. This took around half an hour of trial and error as I kept accidentally inverting my plane and came within a hair’s breadth of smashing it into the ocean several times; it’s really not the best way to kick off a game like Project Wingman, whose entire USP is that I don’t need several hundred pounds’ worth of HOTAS gear and an actual flight license in order to play it. This is supposed to be an accessible flight sim, one which makes significant concessions to the fact that it is a videogame and not real life — such as being able to fit 200 missiles onto a single plane — in order to keep the action fast and fun. I haven’t had to rebind keys in years and I didn’t appreciate that the first thing Project Wingman made me do was half an hour of bureaucratic administration before I could get to enjoying the game proper.

Still, I suppose the nice thing about a game starting off badly is that it can only really improve from there, and so it proved with Project Wingman. The premise is suitably barmy: the Pacific Ring of Fire erupted and caused a global apocalypse which has taken centuries to recover from. Civilization has now progressed to the point where it has fighter jets, tanks and battleships again (many of which have striking similarities to contemporary military hardware but which have conveniently fake names) except with a few more fantastical things like gigantic “air cruisers” studded with turrets and the occasional railgun sprinkled in, and also mercenary companies are apparently once again a Big Deal; the player character is a mercenary pilot drafted in to fight on the side of a plucky underdog country that’s seeking independence from the evil future version of the United Nations.

This plot is throwaway stuff intended to provide a connecting thread for the 21 missions of the campaign and nothing more, but it does do this job reasonably well, lending much-needed splashes of colour to what would otherwise be fairly generic combat encounters — for example, there’s a mission that’s around twenty friendly planes fighting against successive waves of enemy fighters which on its own is not the most complex or interesting thing in the world, but the context you’re given is that it was the aerial equivalent of a meeting engagement that snowballed out of control as both sides vectored more and more squadrons into the fight until it involved the majority of the air forces in the region. This is reinforced by the surprisingly extensive range of cockpit radio chatter in each mission, which ranges from standard fighter pilot barks — “Fox Two!”, “He’s got a missile lock!”, “Gun gun gun!” — to lengthier discussions of the state of the current mission and how it fits into the wider war. You’re never unclear as to what’s going on or why you’re doing what you’re doing, which seems like a low bar to clear but it’s one that could have easily tripped up a budget game like Project Wingman, and I appreciate the effort that went into the voice acting even if a lot of it does appear to have been recorded by friends of the developers and/or Kickstarter backers and has the quality to match.

(Project Wingman lets you listen into enemy voice communications as well as your own side, and as the campaign progresses and your slaughterhouse of a pilot gets more of a reputation you start to hear them audibly shitting themselves once they realise who you are. This comes off as a little goofy at times, but I do like it when games acknowledge that the player character single-handedly killing hundreds and hundreds of people isn’t exactly normal and has the enemies react to that appropriately.)

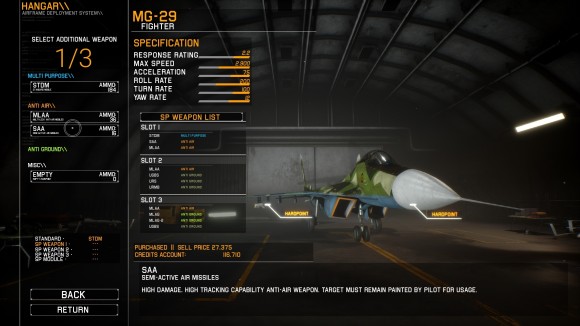

But while it’s nominally fine for Project Wingman’s plot to be just substantial enough to connect up the campaign missions, that’s only the case if the fighter combat gameplay itself is good. I’m not sure that Project Wingman starts that way, because the campaign starter planes are about as aerodynamic as a brick; they’re slow and sluggish and turn with all of the responsiveness of a cruise liner. Fortunately the opening missions of the campaign are essentially just there to let you get used to the various weapon systems with little in the way of opposing aerial threats, and you have the opportunity to upgrade to something that’s a bit more nimble long before the shockingly poor agility of your aircraft becomes a serious issue; it’s just another bad first impression to lump on top of all of the other ones. Once you do have a better plane — or a range of better planes, as you can pick from any that you’ve previously unlocked — Project Wingman opens up a bit. Every fighter in the game comes with a default loadout that cannot be removed or changed, consisting of a cannon with two thousand rounds and two hundred “standard missiles”. On top of that you get to pick a set of additional weapon systems that will be dictated by the hardpoints available on the plane in question — interceptors are specialised for air-to-air combat and cannot take any air-to-ground weaponry, while there’s a plane that’s the equivalent of the A-10 Warthog which is nothing but air-to-ground weaponry, and fighters are multirole aircraft that aren’t as good as the specialists in either role but which can do both acceptably well. The mission briefings tell you the approximate weighting of how the enemy forces are split between ground and air targets, and you have to pick your plane and loadout appropriately based on that information.

Curiously for a game about fighter jets, the range of air-to-air missiles you can take is quite limited. There’s basically only two types: a long range sniper missile that requires you to keep the target painted in the centre of your HUD until it hits, but which will always hit as long as you do this, and a set of fire-and-forget missiles that instantly lock on but which can’t maneuver as well as a jet and which are easily defeated by countermeasures such as flares. To make up for these deficiencies this latter type fires in volleys of multiple missiles per shot — an individual missile might miss, but if you’re firing six at a time at six different targets you should be able to score 2-3 hits. Your supplies of each type of missile are comparatively limited, although only in comparison to the 200 standard missiles you get for free on every aircraft; one hardpoint’s worth of sniper missiles gets you just 16 of them, while the fire-and-forget ones give you 36. When you consider that each mission takes around 20-30 minutes and has you shooting down dozens of targets it’s clear that these are more specialist weapons to be used on high-value targets (in the case of the sniper missiles) or during short windows of opportunity when you’ve boosted far enough away from the main furball to have multiple targets in view at once (for the fire-and-forget ones), and not as your go-to weapon in a dogfight.

Yes, it turns out that there’s a reason they give you 200 missiles and a cannon on every plane, because these are by far the most useful weapons in the game for air-to-air combat. The additional special weapons you can add are nice-to-haves that give you a little more flexibility around how you approach a mission, but every single mission is completable with just that default loadout. At first the “standard” missiles appear to be a bit crap, as you can only fire two at once and they have similar maneuvering issues to the multi-fire lock-on ones I described above; if you fire them at an aerial target that is moving laterally across your HUD the missile won’t be able to turn fast enough to track them and will miss. Similarly if you fire them at a target that’s too far away they’ll have more than enough time to go into a lateral turn and evade the missile. This means you won’t get anywhere by just spamming your 200 missiles willy-nilly; you need to be patient and wait for the right moment, which is when the enemy fighter is heading directly towards or away from you and is close enough that they won’t be able to out-turn the missile. When used like this the missiles are very effective, as a single hit is usually enough to destroy an opponent, and it never takes more than two — and against ground targets all of the weaknesses of the standard missile vanish since ground targets cannot move quickly enough to evade them and firing one means a guaranteed hit unless it hits a blocking piece of terrain.

The cannon is another matter entirely. 2,400 rounds sounds like a lot of ammo, but I ended up using the cannon so much that I often only had a couple of hundred rounds left at the end of a mission — it’s just that good. You only need to score a few hits with it to get a kill, but there’s no aim assist and it’s entirely reliant on your judgement in leading the target, making it most useful in the twisting-and-turning of a close-range dogfight where a missile would just miss. Assuming your fighter has a faster turn rate than your opponent, you wait for them to make a turn, lead them by what you think is an appropriate amount, and then feather the cannon trigger for a few ranging shots to adjust onto target. Once they’re hit they’ll change direction pretty quickly and you’ll have to go through the process again, but they can only do that if they survive and the cannon kills things terrifying quickly once you get the hang of it; I was constantly surprised as I switched to cannon to opportunistically soften a target up only for it to be torn to pieces in a fiery explosion instead. It’s also extremely satisfying to use for strafing ground targets, although this is something of a waste of ammo as ground targets are so easy to kill with missiles.

Of course in practice you’re not dealing with a single enemy plane but dozens at once, and so the proper dogfights are considerably more chaotic than my ideal scenario above. Most of the time you’ll be trying to focus on one specific enemy while evading fire from five or six more — you do have friendly planes on your side in most missions and the enemy AI is less dogmatic about preferentially targeting the player than it is in, say, Call Of Duty, but the sheer weight of numbers means you still end up having to deal with multiple incoming missiles at once — in fact, in the later missions there are so many enemies that you’ll never not be missile-locked until they’re all dead. You have countermeasure flares which can instantly break all incoming missile locks, but they’re on a cooldown and so only offer periodic protection. Since enemy missiles have exactly the same maneuvering weaknesses as yours do, the actual countermeasure is the same as it was in Afterburner all those years ago: burn to maximum speed and turn as tightly as you can so that the missiles can’t keep up with you.

So Project Wingman’s aerial combat is less a matter of leisurely lining up your target for a kill than it is snap-shotting missiles at jets as they flash across your screen and using any brief moments of calm to try and score hits with the cannon. Sometimes you’ll be drawing so many missiles in the middle of a furball that it’s a good idea to boost away from the combat so that you can deal with anyone specifically targeting you, and then turn back towards the main engagement; this is a great opportunity to use your more specialised long-range air-to-air weaponry to get some bonus kills and thin out their numbers a little more, but once you’re back in the thick of things it’s back to the cannon and standard missiles again. Most of the time this process, though a little simplistic, is fantastic fun; once you’re out of the garbage starting fighters and into something with a little more speed and precision you can take advantage of the excellent flight model to pull off some pretty incredible stunts with just the default weapons, slamming a pair of missiles directly into somebody’s face before adjusting your trajectory at the last moment to fly through the explosion and nail their wingman with your cannon. Project Wingman looks a bit rough around the edges — certain elements of the terrain are one step away from being 2D sprites — but that’s because the developers understand you’re going to be spending far more time looking at the sky and enemy planes than you are the ground, and so that’s where they’ve spent most of their effort. There’s good modelling of clouds and weather, missiles leave persistent trails in the sky that tell you just how intense a dogfight is, and the explosions are devastatingly pretty. The campaign missions are pretty varied too, ranging from supporting a friendly paradrop onto an enemy airbase, to a solo raid on their air defence network, to a battle that’s split between destroying an enemy fleet while a storm rages around you before flying above the cloud cover and mopping up their air forces beneath a clear blue sky. When it is working, Project Wingman works marvellously well.

This is usually when I’d drop in a big “unfortunately” and spend the rest of the review slating a game, but for once I don’t feel like doing that. Project Wingman has many structural and compositional issues beyond that unpleasant first hour that I found rather puzzling, but the only really major problem it has that’s worth mentioning in detail is that it’s rather overfond of bossfights against enemy super-squadrons or individual aces. In 90% of the game the chaotic turning battles that comprise Project Wingman’s dogfights are bearable because you’re trying to line up just one good shot. Once you get it you get the payoff of a kill, and you move onto the next target fuelled by that little dopamine hit of watching an enemy fighter explode. The bossfights break this paradigm by having each enemy aircraft take eight or twelve missiles to kill, and being stuck in a tail chase with a single opponent for that long crosses the line from being challenging to downright idiotic. It’s not like they’re particularly threatening opponents, either, since all they have are missiles — easy to counter or dodge — and later bosses have railguns that leave damaging trails behind in the air but which are easy to avoid. They’re just not interesting to fight, which is not a good thing to say about a combat encounter that can go on ten or twelve times longer than usual; all of the higher-level decision making and intelligent use of weaponry that can turn a regular battle in your favour is thrown out of the window here, and this is a big problem towards the end of the campaign when it throws several of these boss encounters at you in quick succession.

(The particularly puzzling thing about this is that Project Wingman already has big tough enemies that take a bit of work to kill in the form of the air cruisers and the various navy forces that occasionally show up. Each cruiser type is studded with multiple targetable turrets which must be killed one by one before the cruiser itself can be damaged, effectively acting as ablative armour. Not only is this a much more interesting problem to solve as you try and remove the turrets without blundering into the cruiser’s major firing arcs, but it provides an additional opportunity for your specialist weaponry to shine as firing six fast-locking missiles at once usually results in six dead turrets, and you can even take a specialist anti-ship missile that can ignore the turrets and directly strike at the cruiser instead. I don’t understand why this concept wasn’t worked into a more significant bossfight instead of relying solely on one where you fly round and round in circles hoping for a missile lock.)

Other than the bossfights, Project Wingman’s flaws, while numerous, did not materially diminish my opinion of the game. For example, there’s far more weaponry available in the game than I’ve described here — unguided bombs, cluster bombs, several additional types of gun pod etc. — but I never used them, either because (in the case of the bombs) they required far too much time to line up on the target when I could achieve the same result with two standard missiles in a fraction of the time, or because (in the case of the gun pods) they were only available on the A-10 equivalent which is far too slow to bother with outside of one very specific mission where your aerial opposition is extremely light. The voice acting started to break down towards the end of the game, and a curious thing Project Wingman did was expecting me to remember who its cast was while having everyone voiced by extremely similar-sounding actors; a huge open goal that it missed (that I think would have been very achievable even with its tiny budget) was not having each subtitled line of voice comms be accompanied by a static pilot portrait that would better allow me to establish some sort of visual identity for its characters. Each of the campaign missions clocks in at around 20-25 minutes, which doesn’t sound that long but which turns out to be a little inconvenient when there’s no mid-mission checkpointing, your plane is only slightly less fragile than your enemies’ (it takes four missiles to kill instead of two), and Project Wingman loves to throw in the hardest challenges at the very end of a mission when you’re likely only a single hit away from having to do the entire thing all over again. The only reason I’m not complaining about that rather more loudly than I am is because I somehow only died once in the entire campaign.

The important thing, though, is that these all ended up being relatively peripheral flaws of the “this could have been executed/implemented better” variety rather than anything fundamentally wrong with the core gameplay of Project Wingman, and it’s why I’m inclined to cut Project Wingman a break even after that bad start. The 21 missions of the campaign are mostly engaging, mostly enjoyable and do not outstay their welcome, taking around 9 hours to work through them all; if after this you want more Project Wingman there’s also a more freeform roguelike campaign mode available that provides some basic structure for what amounts to a series of skirmish missions; That the idea of playing this is not an unappealing one to me says a lot about what Project Wingman does right in spite of all of the things that it does wrong. If nothing else, it’s a great example of what an indie developer can achieve by focusing their resources where they can do the most good; anything that’s not the fighter combat has a functional, cost-effective implementation with very few bells and whistles beyond what is required for it to support and enhance the fighter combat, which is exactly what I wanted from Project Wingman. Sometimes that implementation falls short in painful ways, as with my initial experience with the tutorial and the controls, but by and large Project Wingman gets the important things right; it’s very obviously an indie game with few surprises that does exactly what it says on the tin, but given some of the dross I have sat through recently I’m perfectly fine with a game that’s fully aware of its limitations and which focuses on trying to excel within them instead of trying to push the boundaries into AA-space and falling flat on its face as a result.

- I recently tried Microsoft Flight Simulator which did the same thing, which makes me think this is more a problem with me than it is Project Wingman. I still think it’s uncomfortable to deal with, though. ↩

This sounds very Ace Combat-y indeed. You are correct that Ace Combat is strangely story-heavy. As a franchise, it has a bizarre, complex backstory that informs byzantine sagas of fighter aces distinguishing themselves in a fictional world filled with real planes and sci-fi accoutrements. I don’t know how widely released the remaster was, but if you ever get the chance to play Ace Combat 5, I recommend it. It presents the series in its best light.

Imagine not wanting to play Ace Combat because of the cutscenes! Ace Combat has just the right amount of pseudo-realistic military mumbo-jumbo and anime hijinks in order to get you hyped for the next dogfight.

“Turning was locked to the trigger buttons” – I havent played the game yet, but I wonder if you mean the rudder controls here, especially after mentioning Flight Simulator. So, with aeroplanes you roll to turn, to oversimplify this, the plane is pulled up by the lift generated by the wings right? So if you roll in a direction then you will be pulled in that direction. The lift generated by the large wings is more powerful than the one created by the tiny vertical control surface, that is called the rudder.

The flightstick in a plane controls the control surfaces on the wings. That will be your left stick. The rudder on the vertical stabilizer is controlled by legs through 2 pedals. That is a bit similar to how the trigger buttons are used on a controller. I hope it makes sense this way.

In real life the rudder serves to counteract the torsion that is created by the roll. This is because during the roll the 2 wings have different angle of attack which causes the nose to drop. So in a real life and a proper sim, the rudder is used in the opposite direction of the roll/turn.

There are some other usecases for the rudder but I would not bother you with that now.

Ah, I understand that it’s trying to simulate a aircraft rudder and it actually made sense in Flight Simulator which is, as the name implies, more of a *simulator* — I didn’t rebind the controls there. However there’s nothing realistic about Project Wingman’s flight model and I was expecting a more arcadey control scheme. Now that you’ve laid it all out there I’ll concede that it probably does make a bit more sense for Project Wingman to use a more simulator-oriented control scheme since that’s probably the sort of audience it’s hoping to attract, but at the same time when I’m playing a game that expects me to be firing guns I expect the gun controls to be on the triggers. That’s more what I was complaining about here than anything else.

(Also you’re right that the rudder turn effect is tiny in comparison to rolling — in Project Wingman it’s still very useful for making small adjustments to your aim, though.)