There are many boardgames that would benefit greatly from a computer game adaptation. Ticket to Ride is not one of them.

This isn’t the fault of the developers. Their adaptation of TtR is a decent facsimile of the boardgame; it was originally developed for the iPad and it shows in the controls, but for once this is entirely reasonable as it’s a fairly intuitive representation of what you’d do when playing the boardgame. The problem is that Ticket to Ride itself is far too simple. It’s a light boardgame designed to be played in an hour or so with very few rules and components to keep track of. The great strength of computer game adaptations is that they automate the rules and components side of boardgames, but if that side was pretty much non-existent in the first place then automation adds little to the experience — and in Ticket to Ride’s case it actually detracts from it because it exposes the simplicity of the game for what it is.

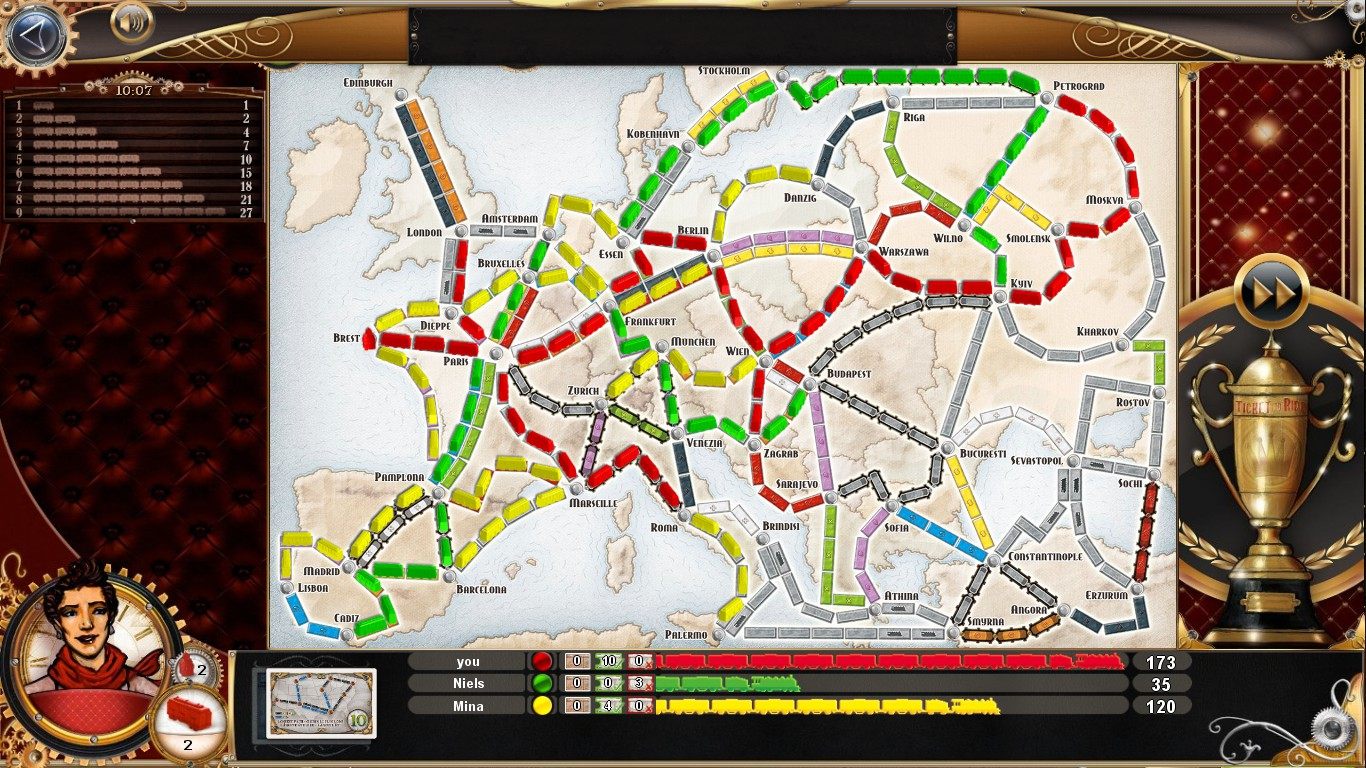

Ticket to Ride is a game about drawing pretty coloured train wagons from a deck of cards and then using sets of similar coloured wagons to lay track down on the playing board, which looks like this:

You can do one of three things every turn: draw two wagon cards, either from the set of five revealed cards in the top right or blind from the deck; play wagon cards to lay track; or take new tickets for new routes to fulfil. The eponymous tickets are – predictably – what drives Ticket to Ride. You pick one or more tickets from a selection given to you at the start of the game, each of which names two cities on the board. Your job is to join up these two cities with a single continuous track. If you manage to do this you score the number of points printed on the ticket. Joining up two cities which are close together will only score five or six points, whereas connecting two cities on opposite sides of the board can score twenty or more.

However, there is a catch. Any tickets in your hand which remain unfulfilled at the end of the game (which rolls around when somebody runs down their stock of 45 track pieces) will have their points value deducted from your score, making every ticket in your hand a potential liability. And if you elect to take more tickets during the game, you have to take at least one of the three presented to you, even if they’re all cities on the other side of the board well away from your established track network. Taking more tickets is therefore decidedly risky, and becomes increasingly so as the end of the game approaches and you have less and less time to build the required track. Balanced up against that is the hope that you might be lucky enough to draw some tickets which you’ve already built the track for (this happens a lot, especially if you’ve built a track all the way across the board), in which case the new tickets are pretty much free points.

This risk/reward mechanic that’s tied up in the tickets is probably the most interesting part of Ticket to Ride. The actual process of laying track is almost absurdly simple. Potential routes you can build will be picked out in segments of a particular colour, or else in anonymous grey chunks. Each segment represents a wagon card you have to play to lay track on that route; four orange segments separating two cities will require four orange wagons to link those cities up. Grey segments can have any colour wagon played to lay track there, with the only requirement being that four grey segments will require any four wagons of the same colour. There are joker cards in the deck which can stand in for any colour wagon, and the lack of any hand limit means it’s entirely viable to keep drawing cards until you’re ready to start laying track along your desired route.

That is, unless some other bastard has laid track there first. Ticket to Ride can accommodate anywhere from two to five players, and with five players the board starts to get positively crowded. Some routes have double track allowing two players to make a connection and it’s almost always possible to find an alternate route to your destination, but this will take time; time you almost certainly do not have if you want to win. So there’s a balance here: do you start laying track early, grabbing the best routes but possibly tipping off other players as to where you want to go? Or do you bide your time, amass a good stock of cards and then blitz your way across the board in a flurry of track-building? The flipside to that is that one of the destinations on your tickets may be cut off entirely by other players, ensuring you take a big points hit for your tardiness.

That’s how the boardgame version of Ticket to Ride plays. The computer version sharpens this simple gameplay down further to a brutal nub of efficient routefinding, but if you’re playing against the AI several weaknesses in the formula become apparent. First is that the AI is reasonably competent but has no concept of advanced human play like blocking other players, meaning it’s pathetically easy to strangle the computer’s routes while driving your trains wherever the hell you want them to go. I have won every single game I’ve played against the AI, and while it regularly gets within 10-20 points of my score it’s always 10-20 points below me. There’s little challenge to be found in the solo play here. There is a certain amount of pleasure to be derived from breaking the game to your will – my current record after a couple of hours of play stands at ten fulfilled tickets – but after a while you start wondering what’s next. And the answer to that question is: not much. The single map of Ticket to Ride is something that’s taken for granted when you buy a board game. In a computer game it seems like a ridiculous limitation since after your tenth play you’re going to have seen pretty much everything that board has to offer, and when each game takes just 10-15 minutes that’s not a huge amount of playing time. There are other, more complex boards available as DLC – you get the Europe board for free if you buy before the end of May, which provides a slightly meatier playing experience – but even these don’t prolong the game’s lifetime that much. I suspect that if you want to get your money’s worth out of Ticket to Ride you’d have to venture online to play against other humans; however, it definitely loses something when you can’t see the other players and revel in their despair as you block their trans-American express with a single purple wagon.

Simplicity can be a boon for a game – hell, it’s the sole reason Minesweeper has managed to endure two decades as a Windows freebie – but there’s also some level of depth required that I’m not sure Ticket to Ride has. It always seemed like light, end-of-evening fare to me; a palate cleanser after playing the more demanding games, and I’m a little puzzled as to why it’s the palate cleanser they adapted and not those more demanding games. Automating those would make them more accessible since I wouldn’t have to fiddle with three centimetre-thick rulebook and a zillion a little counters, but here? Here it seems somewhat redundant. Worse, it actually seems counterproductive. Despite the excellence of its virtual presentation Ticket to Ride loses a lot of its charm when you take away the physical experience of handling the board and the playing pieces, and it’s not something with the variety to stand up to extended play in the way that, say, Through The Ages or Agricola* probably could. It does have one great advantage over the boardgame version: it costs £7, whereas the boardgame will set you back £25-30. However, like the boardgame it can only ever supplement the more substantial games in your library. It cannot replace them.

*Actually this would be the worst thing ever. I love Agricola but it doesn’t need to be made more clinical than it already is.

“I’m a little puzzled as to why it’s the palate cleanser they adapted and not those more demanding games”

Because it’s Days of Wonder doing their usual job of doing digital version of all their big sellers. Memoir 44 and Small World also have digital counterparts, and both would probably stand up better than Ticket to Ride to repeat playings. Nothing else in their catalogue has nearly as much weight behind it (all those 3 have obscene numbers of expansions).

And by “weight” you mean “DLC potential”. Memoir 44 would have been perfect but they went the pay per play route with it, which was very disappointing. I’d happily have paid £7-8 for a standalone version.

I agree with you thoughts concering Ticket to Ride. It is definitely best as a board-game. I wouldn’t consider playing a digital version of it. It is best enjoyed at the kitchen/living-room table.

[...] of two in terms of raw power. To be fair to Hero Academy it’s not the only iOS port to do this as Ticket to Ride had the same problem, but once you were over that initial barrier Ticket to Ride’s presentation [...]

[…] right kind of boardgame for one of these ports. Years ago I bought the Ticket To Ride port — reviewed it on this very blog, in fact — and by removing the physicality of it and reducing it to a set of raw mechanics it […]