Ah, finally, an actually good destruction physics game.

Hardspace: Shipbreaker successfully scratches the itch that went mostly un-scratched by Teardown a few weeks ago: namely, presenting me with a very large object, setting me the goal of ripping it to shreds, and leaving me to figure out the how of it on my own. The premise is that you’re a salvage worker operating a shipbreaking yard in high Earth orbit, and so the very large objects in question are spaceships, which you have to methodically deconstruct using your futuristic laser cutter and your magic space grapple. There are three bays surrounding the yard: a green barge for valuable components such as computers and door consoles, a blue processor for the hard armour and structural reinforcement making up the outer hull of a ship, and a red furnace for the bulk materials surrounding the inner compartments. Your job is to rip successive bits off of the ship and deposit them into the correct bay; doing so causes the salvage completion meter at the top of the screen to increase in proportion to the value of the component you just salvaged. The salvage meter is divided into up to nine segments, and completing a full segment gives you a money and XP reward for unlocking new ships and salvage tools — but you need to be careful that you don’t destroy too much of the ship in the process of salvaging it, either through careless use of the laser cutter or by flinging the wrong components into the wrong bays. The salvage milestones might be evenly spaced out along the salvage meter but the rewards you get for them are not equal, with higher percentages of salvage value yielding higher rewards. In order to receive the full set of salvage milestone rewards for a ship, you will need to recover more than ninety percent of its value intact.

That’s the basic goal, then, and it’s both harder and easier than you might think. To get you used to the basic concepts of salvaging, Shipbreaker starts you off with tiny ships that are the equivalent of space taxis. These have no significant hazards to speak of and are designed to teach you how the cutter and grapple work and how best to use them. The cutter has two modes: a pinpoint laser that will vaporise the component it’s aimed at if you hold it on target for long enough, and a wide-beam version that cuts a horizontal or vertical line across the screen and which can be used to carve out big chunks of ship. The catch is that the cutter only works on the “soft” internal materials of the ship and not on any of the harder outer hull, and in order to separate the two you need to get inside the ship via an airlock, find a way into the void between the inner and outer hulls (often by making a hole with the cutter), and start sawing away at the yellow cut points connecting them together.

Once you’ve managed to detach a bit of the outer hull it’s the grapple’s time to shine, and this also has two modes. One is basically the Gravity Gun from Half Life 2; pointing it at a free-floating component and holding down the mouse button causes a grapple beam to shoot out and attach to that component; from there you can drag it around, reel it in towards you (or reel yourself in towards it, as the game does take notice of relative mass and you’re not going to be able to exert much force on a 100-ton piece of hull plating), or fire it off towards the appropriate salvage bay. It’s the second mode the grapple has that’s most interesting — and most useful — though, as the grapple also allows you to materialise an energy beam that will tether two separate objects together. To do this you point at one end of where the tether should go, hold down the right mouse button, drag the tether to where the other end should go, and release. It’s very quick and easy to do, and because the tethers have infinite range you don’t have to worry about positioning beyond giving yourself line-of-sight on both things you want to connect with the tether. Tethers exert a constant force pulling the two objects they’re connected to together, so if one end of the tether is stuck to an immovable object, such as the edge of a salvage bay, the thing stuck to the other end will slowly move towards it. You quickly learn that while the direct grapple ability cares very much about how heavy you are versus how heavy the thing you’re trying to move is, and is thus only useful for moving small pieces of ship around, the tethers are capable of shifting much larger objects. Tethers are what you’ll use to throw bulk materials around 95% of the time, and the grapple itself is reserved for small, valuable components like computers and door consoles that can be quickly removed and thrown into the salvage barge.

Already there’s quite a satisfying process taking shape here. You go into a ship, separate the outer hull from the inner compartments by sawing through those connecting beams, and then head back outside and materialise a whole bunch of tethers one after another to yank the hull into the processor bays – do it fast enough and the whole ship seems to split into two halves, like you’re deshelling a peanut. The particularly nice thing about using tethers to move things into the bays is that they’re mostly hands-off, too; once you’ve learned the best points to attach them to you can set them up and then go off and start dealing with the rest of the ship while the tethers do their work, and then a couple of minutes later when the tethered material finally arrives at its destination you’ll get a “Material accepted for processing” radio message and your salvage meter will start to creep up with a pleasing progress sound effect. If you’ve done this with four or five bits of ship (or one particularly massive one) this will happen several times, each one delivering the small dopamine hit of knowing you did your job right. The process of deconstructing a ship also comes with a bit of the fascination of those classic Dorling Kindersley cutaways, as you progressively remove the larger exterior components, then the hull, then the valuables from the interior, gradually peeling back layer after layer to get at the juicy salvage within.

However, real-life shipbreaking is dangerous work, and the outer space version is no different. With each ship type you unlock after the first, Shipbreaker introduces additional hazards that you have to minimise or avoid. Pulling out electrical components like batteries and power packs can cause electricity to arc to nearby surfaces — and yourself, if you’re not careful. Using the laser cutter anywhere near fuel lines is suicidal unless you’ve drained the fuel lines first; the laser cutter itself can also set things on fire with a clumsy shot. Later ships come with thrusters and reactors that each need to be managed in specific ways, with one type of thruster actively requiring you to cut through four fuel lines and then dash past a bunch of burning pipes before the fire reaches the fuel storage and the entire thing explodes. The reactors will instantly go into meltdown once you’ve removed them from their housing and you’ll only have a limited amount of time to get them onto the salvage barge, so you need to have cleared a path that lets you quickly extract it and then tether it in.

And finally, and most lethally, there’s explosive decompression to think about. Cutting into any compartment that is still pressurised will cause all of the atmosphere inside to rush out through the hole you’ve just made, with three potentially deadly consequences. First is that you yourself can be blown into space by the explosion, or (worse) into the salvage furnace. Second is that if you’ve chopped away a lot of the ship’s mass — such as by removing the outer hull, which seems to make up around 50% of the mass of any ship — the ship itself will be thrown across the salvage yard by the sudden outrush of air, and if you’re not prepared for it to suddenly turn itself into a ballistic object you can find yourself crushed beneath a bulkhead. And third is that even if you prepare and mitigate both of those outcomes, there’s no avoiding the decompression throwing everything inside the compartment around in a particularly energetic way. This is the most unpredictable thing you will have to deal with in Shipbreaker. Sometimes the decompression will cause no damage. More often it will destroy a few valuable components, but not enough to make working around the decompression effect worthwhile. Occasionally it’ll smash a lot of particularly expensive equipment like hydroponics bays, which incurs enough negative value that you have to be really careful salvaging the rest of the ship. But the reason I was always particularly careful around decompressing the later ships in particular is because of one incident where I started my salvage of a ship by casually removing an exterior thruster cap to extract the thrusters; this exposed the reactor compartment to vacuum, and the resulting decompression somehow yanked the reactor out of its housing starting the meltdown timer. This meant I had to very quickly enter the ship, cut all of the the support beams, tether away a piece of the hull to make a hole large enough for me to get the reactor through, remove all of the panelling around the reactor, and then toss it into the barge with mere seconds to spare before it went critical and obliterated me and a large percentage of the ship.

Unfortunately while that was an agreeably tense experience it’s also as tense as Shipbreaker ever got, and it was very much the exception. Most of the above hazards are trivial to work around as long as you’re methodical about stripping the ship. Electrical arcing is only dangerous if you’re jammed up right close to the thing you’re removing, and even then it won’t kill you. Ditto for fire, which you’ll only have to deal with in any real capacity when you’re doing those exploding thrusters; the pipes inside the thrusters shoot out jets of flame that you’re supposed to avoid while jetting to the shutoff switch, but I just didn’t bother because the amount of fire damage I took wasn’t even close to being lethal. Fuel pipes have big lights on them telling you when they’re full of fuel, and it’s the work of a few seconds to locate the flush switch rendering them safe. Extracting the ship’s power battery requires you to do three very easy quicktime events to remove fuses, after which it’s rendered totally inert. The tutorial for radiation filters tells you to remove the inner panel from the interior compartment, cut a hole in the ship to the outside, carefully extract the filter and move it through both holes like you’re playing one of those buzzer games with the long wire track and the metal loop; if the filter is knocked or jostled at all it’ll leave behind a delightful cloud of radioactive particles to ruin your day. Except once you’ve removed the outer hull it turns out the filters are also easily accessible from the outside of the ship, and all you have to do is cut away the frame holding them in place and pull them free with zero chance of them hitting anything. And the reactors are easily worked around by just not pulling them out of their housing until you’ve salvaged practically the entire rest of the ship and have plenty of space to work with.

This is disappointing, but not fatal. The hazards are a bit crap at actually being hazards — in fact the most dangerous item in the game is none of the things listed above, but is instead your own grapple beam; if you reel in a small object that’s far away too quickly it’ll come flying at you at an appreciable fraction of the speed of light and smash your spacesuit faceplate, killing you very quickly through asphyxiation unless you’re close enough to your hab to crawl back into the airlock before your expire. But while they are simple to work around, you do have to work around them. You can’t just blow holes in everything and throw the resulting bits into the right bays – at least, not without making the ship safe first. So the first run of each ship type is quite slow, as you spend time exploring and figuring out exactly what you’re dealing with here, and making a checklist of the things you need to do to extract maximum salvage value and in what order. Subsequent runs get faster and faster as you optimise until you’re stripping a ship down completely in less than half the time of your initial attempt, not triggering any hazards and achieving a maximum payout every time. In fact as long as you’re being careful like this it would be quite difficult to not get a maximum payout; I only failed once, when I decided to see if I could cut through a fuel line separating two valuable components that needed to go into different bays. I thought the fuel line was empty, but it was not, and while I survived the subsequent explosion it trashed 10% of the ship’s value in one go. I treated fuel lines with a bit more respect from that point onwards.

So I think the hazards do serve a purpose of providing some additional structure and sequencing to what would otherwise be a fairly straightforward task, even for the largest ships. They can only prolong the experience so far, but fortunately Shipbreaker is quite good about regularly introducing new ship types at right about the point where you’ve fully optimised the last one; I never ran a single type of ship more than three times in my 22 hours with the game, and while a “new” ship you’re presented with is often a remix of an existing hull type rather than a fully new thing, it still injects enough variety into the campaign that the process of actually breaking the ships rarely feels tedious or repetitive. That process is helped along considerably by some absolutely tremendous presentation, from the astonishingly good soundtrack being piped in over your suit radio — which dynamically switches to more appropriate tension music whenever you’re doing something particularly dangerous like darting down the middle of a thruster housing — to the HUD elements flickering and distorting in areas where there’s heavy radiation, to the wonderfully tactile nature of the player avatar you’re inhabiting. They reach out and interact with levers, switches and consoles, bang their helmet whenever their radio gets scrambled to try and clear it, and their three-dimensional movement in a microgravity environment takes a bit of getting used to but has a wonderful sense of weight and momentum to it. It’s been a while since I’ve played a first-person game that felt as immersive as Shipbreaker does, and it’s doubly refreshing that it doesn’t once involve shooting a collection of bad guys who are peeking their heads out from cover.

That’s Shipbreaker’s core loop, then. It’s a very good one, for all that it feels a little bit lumpy in places; that process of explore-solve-optimise and the satisfying ship dismemberment mechanics carried the game an awfully long way, to the point where I was fully prepared to forgive a lot of what the game does wrong. And good lord does Shipbreaker do a lot wrong. Most of its mechanical failures are focused around its survival elements; you have an O2 meter and a thruster fuel meter that you have to manage while you’re breaking a ship, and all of your equipment also has a durability rating that steadily decreases as you use it. Obviously if any of these meters reach zero you’re in big trouble, but I never did find out what happens when they do because the mechanics for refilling each and every one of them strike me as being placeholder things you put in at the start of Early Access in the expectation that you’ll figure out later in the development roadmap — only Shipbreaker never did. When you get a low O2 or fuel warning, all you do is fly over from the ship to your hab — this takes about 10 seconds — access the shop kiosk in front of it, and buy an O2/fuel refill. That’s it. That’s the mechanic. I could perhaps understand if these things had exorbitant prices that would take a significant chunk out of your salvage payout, but as it is an O2 refill costs sixteen thousand dollars while salvaging even a teeny tiny starter ship will give you several million, and an endgame ship will provide in excess of thirty million space dollars. Since I am not having to refill my O2 tank 1,900 times during the course of a one-hour salvage operation I do not understand why the O2 management mechanic exists in the game at all. It, and the fuel, and the durability mechanic, are completely meaningless overhead that I would have resented a hell of a lot more if they hadn’t been so trivial to deal with.

Then you’ve got the shift system, which is where we really start to dig into the shit side of Shipbreaker. The setup for the game is that you’re basically an indentured servant for the megacorporation running the shipbreaking yards, and that they charged you for various “services” they provided when you started the job, such as transportation from Earth up to the yard and registering your genetic material so that they can grow spare copies of you in the event of your untimely demise (this being how the game hand-waves away any deaths that might occur during the salvaging process). This has caused you to rack up a debt of a ludicrous-sounding $1.2 billion dollars, and you have to work off the debt by salvaging ships before the corporation will let you quit. All of the expenses you incur during the salvaging process, such as destroyed components and O2/fuel/repair fees, are added to your debt total, and on top of that you get charged a daily rental fee every time one of your work shifts ends.

The base campaign mode doesn’t let you work on a ship from start to finish in a single session, you see; it instead restricts you to fifteen minute shifts, and at the end of each shift it teleports you back into your hab to be presented with a profit-loss statement for the day’s work. The idea here is that taking a long time to salvage a ship causes you to rack up even more debt through rental fees, which is supposed to introduce the pressure of rushing your work to salvage as much as possible during a single shift and perhaps cutting a few corners in order to make sure you break even on the day’s work. Once again, though, the numbers involved have been put into the game at the start of Early Access and then never changed for the 1.0 release1, because the total daily rate for those rental fees is around $330,000. Again, when an early game ship can be completely salvaged in just two shifts and pays out five million dollars, the corporation adding just 10% of that amount onto my debt means I’m still making 90% profit. It gets even more absurd in the late-game when you’re stripping Javelin tankers in just three shifts for a $30 million dollar payout against a $1 million dollar outlay. The rental fees are completely meaningless2, and so the practical effect of the shift system is to force you to look at a pair of loading screens every fifteen minutes, one to get back into the hab and another after you immediately walk across to the airlock and exit again so that you can continue salvaging your current ship.

That is, unless the developers physically lock the door to the hab airlock so that they can force you to listen to yet another piece of Shipbreaker’s terrible, terrible story. Given the premise it’s perhaps unsurprising that the plot is focused around the salvage yard workers unionising to stop their exploitation, and while said premise is incredibly unsubtle, the most cartoonishly dystopian portrayal of capitalism possible, gamers are famously hard of thinking and probably need things drawn out in crayon like that in order to understand it. Despite its absolute mishandling in terms of the mechanics I’m not complaining about the premise at all; the problems largely stem from the fact that Shipbreaker thinks it’s radical pro-union material, but what it actually is is a story about unions written by an idiot with a child’s understanding of how unions actually work, told in the most obnoxious way possible by a character who might actually be an alien in disguise. She’s called Lou, and every so often, usually just after you’ve ranked up your character, you’ll find the doors to your hab locked and a voice message from Lou waiting on your personal terminal. You have to play the message in order to continue, and Lou’s messages are a mix of creepy stalker shit3 and the most unsubtle and simplistic pro-union screeds in the world. You have no option to skip the voice messages, you have to just let them play out which can take several minutes, and just in case you were thinking you could at least review your emails or use the equipment upgrade station while the voice messages are playing, both of these terminals are inexplicably locked off as well. Listening to Lou’s ramblings is all you can do during these segments.

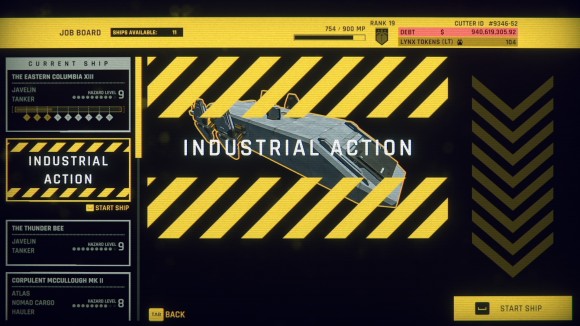

The most annoying thing about the voice messages is that they can strike at any time. If you’re in the middle of salvaging a ship and a shift ends, you want to be able to get back out into the yard to continue salvaging it as quickly as possible as you’ll likely be in the middle of some particularly tricky operation, or halfway down your salvage checklist for that ship. But instead of letting you do this the game instead locks the door and forces you to listen to this audio vomit for five minutes, and by the time you’re freed the enforced context switching has ensured you’ve forgotten whatever it was you were doing. Sometimes you get a run of four or even five shift change intervals in a row where the game repeatedly locks you into the hab and makes you listen to its story, and it’s absolutely maddening to have what should have been a smooth salvage process forcibly broken up like this. Usually if I come across a bad story in a videogame I can just skip it — or I have the option to skip it — which softens the impact, but the fact that Shipbreaker physically doesn’t let you meant I ended up hating its story far more than other examples of the type. After I ranted about it for a bit a friend said it sounded like false-flag propaganda to turn people against unions, and he’s exactly right; that is precisely what experiencing Shipbreaker’s story feels like, the equivalent of being strapped into the Ludovico device from Clockwork Orange and forced to watch the most heavy-handed and infantile take on this stuff until I couldn’t stand it any more, and it was honestly a profound relief when a big yellow button showed up in my ship selection menu saying “INDUSTRIAL ACTION” because it at least meant the game would be over soon.

So my run through the Shipbreaker campaign ended on a decidedly sour note. The core concept is solid and implemented extremely well, despite some leftover physics glitches indicating that said concept is running up against the limits of what’s possible in the game engine and that going any further than Shipbreaker currently does (there’s a subset of fans who are upset that the biggest class of ship you get to deal with is merely Big, instead of Really Big) would result in the entire thing collapsing like a house of cards. While I would have eventually gotten tired of salvaging the ships that are available, that didn’t actually happen during the 20-odd hours I spent with the game so I don’t think there’s all that much wrong with the salvage gameplay. The weirdly unbalanced metagame values do let Shipbreaker down somewhat, but even this is largely fine because they’re at least unbalanced in the direction of being way too forgiving, and thus almost totally ignorable; my complaints there are more that these are obvious missed opportunities than it is because I think they significantly hurt the game. But that dreadful story is not something I can let go; it’s fairly telling that the more time I spent with Shipbreaker’s campaign the more negative about it I became, until I was just glad to be done with it. I’ve not seen a game just casually toss away all of its hard-earned goodwill like this since Death Stranding, and just like Death Stranding it makes Shipbreaker a little hard to recommend to people. I do still think it’s worth playing in spite of all that it does badly, though, just for the concept alone; those first hours with the game before the plot elements have really started to kick in are damn near magical, and while the magic eventually wears off there’s still nothing I can think of that quite matches the satisfaction of systematically dismantling a Shipbreaker ship into nothing. Just, if you do download it, remember to Alt-Tab out during the story bits or otherwise go off and do something else for a bit until they’re finished. Trust me on that one.

- Possibly because so many people complained about the shift system that the developers added a version of the campaign that removed the shift timer completely, as well as the O2 meter. That could explain why it all feels so half-baked, because why bother fine-tuning numbers if players don’t like these mechanics? But then my question would be, once again: why include these things in the game at all? ↩

- In fact the $1.2 billion dollar debt total is much smaller than it sounds. In 74 in-game days of work I’d made $400 million dollars, implying that I could have worked that debt off in substantially less than a year. ↩

- I still haven’t gotten over the message where, totally unprompted, on like the fifth day of work, she said she went on a date with a girl on one of the “Eris platforms”, and that they kissed at the end of the date, but that the date didn’t go any further than that and they didn’t see each other again. She then wonders at length if the girl ever thinks about her. Uh, no, it was one date and it clearly didn’t work out, the usual reaction to that is to move on instead of obsessing about it years later. Not only is this not something that a normal human being would ever think to raise with a co-worker on their fifth day on the job, but it makes me seriously wonder about the person who thought it was a good idea to put that dialogue into a game about smashing up spaceships. ↩

Great review, sums up exactly my feelings (ive only completed 4 ships so far). Playing with o2 on and shift timer off. Super relaxing times for an OCD tidy type of person like me.