Citizen Sleeper is an interactive fiction game where you’re essentially playing one of the replicants from Blade Runner. You start the game having fled from your corporate masters to Erlin’s Eye, a space station cobbled together from the wreckage of an economic collapse a decade prior, and you need to stave off the encroaching breakdown of your cybernetic body while eking out a living on the fringes of this ultra-capitalist hellscape by…

…growing mushrooms?

Okay, the mushrooms aren’t that big a part of the game, but I feel that they are a perfect representation of the design flaws that contribute towards Citizen Sleeper going a little bit off the rails in its final act. Growing the mushrooms is going to be the first thing on my mind whenever anyone asks me about Citizen Sleeper in the future because it’s what I spent the last hour of the game doing, and that’s a real shame because the first four hours are as good as anything I’ve played so far this year.

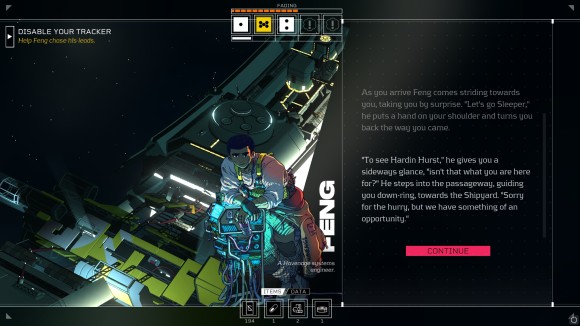

One of the most impressive things about Citizen Sleeper — to me, anyway — is how it does so much with comparatively little. Some people might take issue with my description of Citizen Sleeper as “interactive fiction” and I’ll admit that it’s not 100% accurate since it does have a little more mechanical meat on its bones than that description implies; however, I don’t think I would call it a role-playing game in the sense that you get to define the character you play, as there are only three or four points in the game where you get to make truly meaningful decisions. Mostly what you are doing is visiting various locations on the station to progress individual story threads, which the game calls Drives. This story is related to you via the standard pop-out text panel on the right hand side of the screen, and while you are occasionally prompted for a reaction or a dialogue choice it is extremely, painfully obvious from the way they are written and the way the responses are written that both options that you are presented with are going to end up in the same place. This means that the entirety of the game’s narrative is just you cycling through a collection of text blocks (which is why I’m calling Citizen Sleeper interactive fiction) and while I’m not wholly prejudiced against that kind of game it does raise the question of why you made it a game and not a e-novel or something.

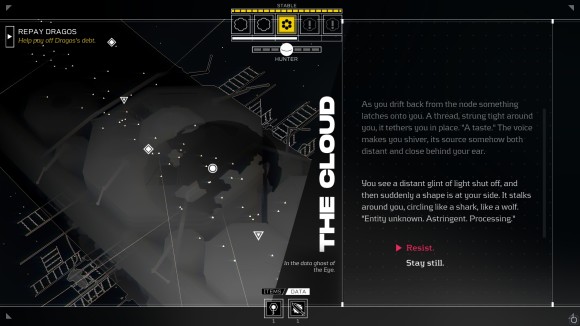

However, Citizen Sleeper is smart enough to dump the majority of its actual game development resources into two things that make the game far more atmospheric and which make the player much more open to buying into its world. First, and most important, is that you can actually see that world the entire time that you are playing it; the text boxes might occasionally pop in from the side and take away focus, but otherwise the screen is devoted solely to showing you a 3D model of the space station that you are stuck on. Since it’s a ring-type space station you can rotate it backwards and forwards by pressing W and S, and you’ll see little icons pop up as new sections of the station hove into view — these are the various locations you can visit. Click on one and it’ll zoom in to show you that location in a bit more detail, and while the 3D models are pretty simple it’s all rendered in a consistent, coherent visual style that’s more than enough for the purposes of the game, which is that this is Citizen Sleeper’s world map. You may not be able to take the camera inside any of these ships or buildings — that side of things is handled solely by the text interface — but seeing them laid out along the station ring as actual physical locations instead of randomly placed nodes adds tremendously to Citizen Sleeper’s sense of place.

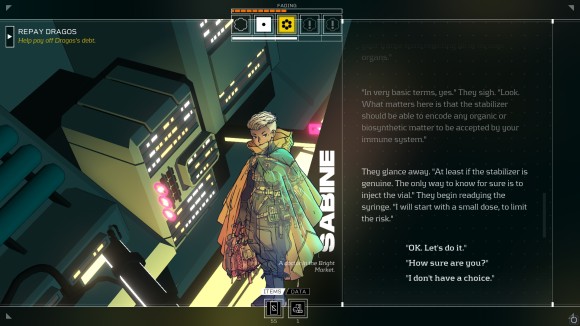

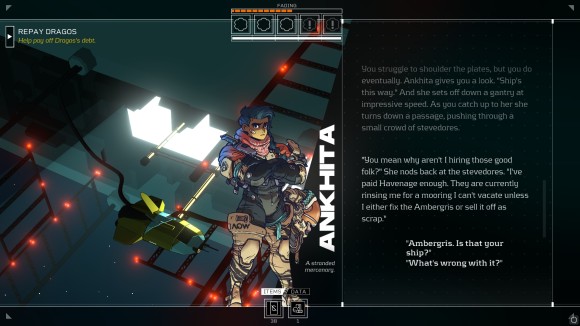

Coming in a close second is the character art. I’ve long held that a set of good 2D character portraits can do an awful lot to prop up a player’s imagination when you’re otherwise forced to rely solely on text for your character interactions, and Citizen Sleeper goes one better by providing at least one piece of full-body art for every significant character in the game. This lets the game do a lot with character poses and outfits — the spacer mechanic floats in zero-G with a mischievous smile, the computer hacker is sprawled over a stack of electronics and just radiates smug overconfidence, the doctor is wearing a see-through poncho that somehow makes her seem standoffish and distrustful — and packs in a surprising amount of detail that’s nicely evocative of each character. This goes an awfully long way towards selling the Eye’s inhabitants as people rather than as quest/story nodes. One strange omission is that while there’s also character art for the player it’s only visible when tabbing through to the stat screen to do your upgrades, and when you’re in the main game interface you’re just a faceless, disembodied entity; this makes it more difficult to build a sense of connection to this robot person you’re supposed to be playing, but also demonstrates just how strong being able to put names to faces for everyone else on the station really is.

And that’s it, really. Citizen Sleeper’s soundtrack is not something I could say that I ever really noticed when I was playing it, which is not to say that it is bad — it’s just going for background ambient synthwave that enhances the mood rather than trying to dictate it. Its UI has clearly had a fair amount of thought put into it also and is functional enough for what it’s doing, although far from perfect. But the vast bulk of the heavy lifting behind Citizen Sleeper is being done by the 3D station model, the 2D character art and the writing, and I truly admire just how far the game gets on those three things alone. It manages to paint a rich picture of the history and culture behind this deep-space sanctuary you’re stuck on while having a fraction of the resources available to bigger games, because it uses those resources cleverly and in a way that lets it generate a large amount of high-quality narrative content for a minimum of development outlay, and without asking the player to shoulder too much of the load themselves to make up for it.

This is a philosophy that also extends to its dice-based survival and resource management gameplay, although I’m a little less gushingly enthusiastic about this side of Citizen Sleeper because it’s where a lot of that frustration in the last hour of the game came from. I said earlier that Citizen Sleeper had more mechanical body to it than the “interactive fiction” term implied, and that’s true both literally and thematically. The idea is that, since you are playing a robot on the run from the corporate authorities and struggling to make a living in an unfamiliar environment, you not only have to scrape together enough money for food to live, but the corporation that made you also made you dependent on corporate-provided medicine as an additional security measure. If you do not find some way to acquire a substitute, your robot body will slowly degrade and become less and less capable. It’s implied that you’d eventually die if you went long enough without taking the meds, although this is another piece of internal tension that Citizen Sleeper never quite resolves; based on the various escape routes and safety valves present in the narrative I do not think that it would ever actually present the player with a Game Over screen, no matter how badly they mismanaged their dice. However, the penalties for just letting your condition deteriorate to the minimum possible level are annoying enough that there’s a significant incentive not to do this even if you’re not actually going to die in the game if you mess it up.

Anyway, the dual needs of food and medicine are represented in game by two bars along the top of the screen, called Condition (which is boosted by taking the medicine) and Energy (which is boosted by eating and drinking). The Energy bar has five segments and will decrease by two segments per day, while the Condition bar has twenty segments and will decrease by one segment per day. In practice this means you have to refill your Energy bar much more frequently than you do your Condition bar, and the game provides many different ways of doing this — but most of them involve buying food for money at a rate of around 5 credits per Energy segment refilled. By contrast you only have one way of increasing Condition available to you at the start of the game: buying those corporate meds off of the black market, which is expensive at 100 credits per go. One dose of meds will completely refill your Condition bar from empty, but in practice you’re going to want to take them more frequently than that thanks to the negative effects of not maintaining both your Condition and Energy at high levels at the same time.

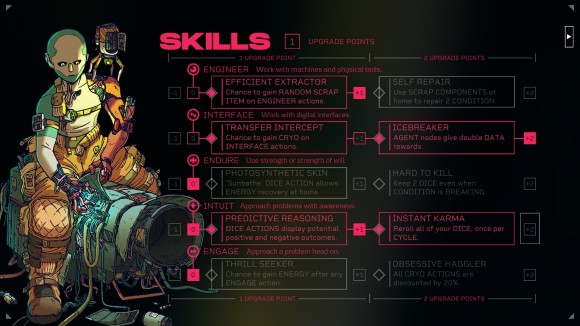

This is because your Condition and Energy levels at the start of a day directly affect how large your dice pool for that day will be. The game uses regular six-sided dice, and at the start of every day you’ll get to roll up to five of them, with each dice representing one in-game action you can perform that generates resources, opens up new areas or advances storylines – working a shift at a bar, repairing busted ships, clearing space for crops in the hydroponics area, that kind of thing. The value of each dice determines how successful each action will be, with positive or neutral outcomes giving you money or increasing progress counters to a greater or lesser degree, and negative outcomes decreasing money or Energy or resulting in a dent to your reputation on the station. A dice roll of 6 is a guaranteed positive outcome, while a dice roll of 1 has a 50/50 chance of being neutral or negative; once they’re rolled at the start of the day they can’t be re-rolled without a special skill perk, so you have to plan out your day and assign your dice to the action slots where you think they’ll do the most good. If there’s an action with a bad negative outcome you’ll want to save your fives and sixes for it for the guaranteed success; ones and twos are spent either on low-risk activities where the negative outcomes aren’t so bad, or else in the game’s hacking layer where they can be used to extract data and security keys from the station’s systems for zero risk.

The catch is that while you get up to five dice — and thus five actions — per day, your Condition level needs to exceed the thresholds required to grant those dice. You only get one action dice per four points of Condition you currently have, and if you let your Energy levels drop too low your Condition will start to deteriorate much more quickly — you need to finish the day with at least two Energy segments in order to avoid this penalty, and this can be challenging when many of the negative action outcomes result in you losing additional Energy above and beyond the baseline two segments per day. So, keeping your Condition and Energy bars topped up means both doing more actions and gathering more resources in a single day, as well as rolling a larger dice pool and having a lower chance of being stuck with crappy low-value action dice that don’t let you do the things you want to do.

At the start of the game, when you don’t have any skill points and you don’t have many station areas unlocked and you don’t know what the best ways of spending dice and gathering resources are, this dice-based action system works tremendously well at impressing on you just what a struggle it is to survive in this unfamiliar new environment. Money and resources are always tight. There are some agonising choices over where to commit action dice, and where to spend your limited funds, and at times it seems like you’ll never get out of subsistence mode, only having a single action dice left over from gathering money and/or Energy to actually progress the story. However, once you’ve spent a few days stabilising and actually manage to boost both your Condition and Energy to maximum, you’ll find that it’s much easier to keep them there; when even a dice roll of 1 can be exchanged for enough money to counteract the daily decrease of your Energy level the maintenance of these bars starts to seem like unnecessary overhead as your continued access to 4-5 action dice per day means you become less and less resource-constrained. The system breaks down entirely once you’ve got a few completed Drives under your belt, as these grant skill points that let you buy permanent perks and dice pool modifiers, giving you even more flexibility around how and where you spend your action dice. By the end of the game I was starting to wonder why being stuck in my robot body was considered such a bad thing, as thanks to the character perks I’d become a post-scarcity organism capable of eating metal, drinking sunlight and sucking money directly out of the datasphere, which had incidentally completely trivialised the entire actions/resource management side of Citizen Sleeper.

And this moment rather unfortunately came at a time when Citizen Sleeper’s narrative was starting to fall apart, too. The game does have a structural problem where there’s no real main story thread for you to follow; it felt more like a collection of 12-13 sci-fi short stories that did a lot to flesh out the backstory of the station and which gave you a window into the lives of the people living there, but which didn’t really advance your story in any way. Because these stories aren’t dependent on one another and can be done in any order, this means that Citizen Sleeper has to deploy drastic measures to ensure the player actually does see most of the content and doesn’t accidentally trip over The End Of The Game. Mostly this takes the form of progress bars and timers, which the game refers to as Clocks. Progressing a story thread to the next stage involves incrementing a Clock by investing (usually) multiple days’ worth of action dice into it; once it’s full, what will usually happen is there’s a brief narrative interlude, and then a second Clock appears that ticks down at a rate of one segment per day. Once that is full, you get to do the next bit of the story.

The time-based Clocks are there as a way of temporarily locking progress on one storyline and forcing the player to go off and work on other ones for a bit; it might be possible to blitz a action-based Clock in a single day with a full dice pool and high modifiers, but there’s no way of getting around the time-based ones aside from waiting out the timer, and so you might as well spend that time usefully by progressing a different storyline. For the first four hours of the game this actually worked wonderfully well. The quality of Citizen Sleeper’s writing is consistently “good” rather than “great”, but it’s given a big boost by the smart decisions around location and atmosphere that I mentioned further up the review. It has few new observations to make about the evils of capitalism that haven’t already been covered at length in other sci-fi/cyberpunk fiction, but it’s still worth restating them just in case there’s somebody out there who somehow hasn’t gotten it yet, and what I did like about Citizen Sleeper was its strong belief in the inherent goodness of people once they’re separated from the systems that encourage them to behave like monsters. There are very few outright villains in the game that aren’t faceless corporations manipulating people from star systems away, and despite your replicant status marking you out quite obviously as an Other (you look like a literal robot rather than the human-form replicants of Blade Runner) the typical response from the characters you’ll meet during your time on the Eye isn’t one of fear or prejudice, but they’ll instead try to help you on your way. Citizen Sleeper doesn’t really have much of a sense of humour; everything’s played pretty much straight, and it prefers to soften its portrayal of a system where you are quite literally a slave to capital with small human moments that reaffirm your faith in people. I preferred the incisive sharpness of Disco Elysium, but Citizen Sleeper’s approach to narrative and world-building is no less valid, and only slightly less effective.

However. As satisfying as knocking off all of those stories is, once you’re about four hours in you’ll find that you’ve finished most of the stories on offer, and that the only ones left all seem to terminate in a mushroom farm that’s the last area you unlock on the station. There’s no less than three separate stories that demand mushrooms or mushroom-related products, and one of them leads to the end of the game. The problem is that you need specific kinds of mushroom for each one, and in order to grow mushrooms you need to:

- Invest actions in harvesting fungus spores from a nearby area

- Plant the fungus spores in the mushroom farm

- Wait out a four-day Clock

- Harvest the mushrooms.

What type of mushroom you receive after harvest is determined by RNG at harvest time, and my problem was that the game just would not give me the right type of mushrooms needed to progress the required storylines. Even when it did, all it did was activate another time-based Clock that I had to wait out before I could do anything else. It took three separate mushroom harvests — 12 days of in-game time, in a game that up until that point had only been running for around 30 — until I could get all of the mushrooms required for all of the stories, at which point I discovered that I had to wait out one final 8-day Clock with nothing else to do. And I had to do it while engaging in the drudgework of maintaining my Condition and Energy, too (any interesting decisions inherent in the action dice system having long since vanished thanks to my robot having one foot inside the technological singularity) as I didn’t know if there were further story stages waiting for me after that Clock expired. This meant that my last hour with Citizen Sleeper — my final memories of the game — wasn’t of the cool atmosphere or the world or the strong storytelling, it was of now-tedious daily action dice management and then repeatedly clicking “End Cycle” so that I could grow and harvest these bloody mushrooms.

On one level I get why there are so many timers at the end of the game: Citizen Sleeper really does not want you to hit it without having seen everything else it has to offer. Because the stories can be done in any order it also has to allow enough time for people who have been single-mindedly following one plot thread to go off and do a few other things, and I imagine that these people will have a much better time with Citizen Sleeper’s ending because they won’t be stuck with nothing to do, like I was. That doesn’t change the fact that this is a terrible finish for what was otherwise one of the best games I’d played this year, a real sour note on which to end both Citizen Sleeper and this review. And that’s a real pity; it’s admirably well-pitched for 80% of its length and while the action dice system runs out of gas about halfway through the game that’s really not so much of a problem until the story does too. Until then it’s a fantastic take on a narrative adventure, one which isn’t going to win any awards for originality but which excels in its execution, and whose message doesn’t penetrate quite as deeply as that of Disco Elysium only because it’s not delivered with quite the same barbed wit. And given that Disco Elysium is the best narrative RPG released in the last twenty-odd years, the fact that I’m mentioning Citizen Sleeper in the same sentence in a largely non-derogatory way means it’s probably doing something right.

“Citizen Sleeper really does not want you to hit it without having seen everything else it has to offer.”

It’s deeply flawed in its execution of it.

I (without realising my actions were doing so) brought about the ‘big spaceship’ ending, while I still had 5 “drives” (goals) left that I’d wanted to do.