This is the beginning of an infrequent column on board games. It won’t be weekly like my other stuff since I’m nowhere near as sure of myself as I am when I talk about video games or science, and since I tend to only play individual games once or twice it’s tricky to assess whether they’re good or not. This makes it rather hard to come up with decent material for a column, so I’ll only publish them as and when I can think of something to write about.

Ah, the deck-builder. It’s a game type with a relatively long and venerable history, but one that has recently come into vogue in mainstream boardgames with the advent of what I’d describe as the “disposable” deck builder. Previously in something like Magic: The Gathering you’d build your deck of cards before the game and be stuck with those cards and those cards only for its duration. The Magic approach allows players to fine-tune their deck according to a certain strategy which makes it a fairly deep game, but it also has a major problem thanks to its payment model, which is similar to the payment model used by social media games the world over. In Magic you can buy fixed decks which have the same cards in each type of deck, but these are only intended to start you off – the free sample, as it were. The real meat of Magic is to be found in the so called “booster” decks. This is where the most interesting cards live, but what you get in an individual booster deck is almost completely random. In order to perfect a certain strategy you’ll probably need a certain booster card, but getting this card is a complete crap shoot unless you happen to be rich enough to either keep buying booster decks until you luck into it or else buy it off another player who already has it.

Thus Magic is an inherently asymmetric and uneven game – and not in a good way, either. It pretty much invented the concept of “pay to win” now taking shape amongst the various free MMOs you can find on sites like Facebook; the more money you invest in the game, the more stuff you can do and the better the chance you have of winning. What distinguishes the recent generation of deck-builders from something like Magic is that they attempt to level the playing field by making players build their decks from a common supply of cards as the game progresses, while also introducing various other mechanics to ensure the game retains some degree of replayability. In theory everything you need to play multiple games will be included in the game box, with no other additional investment required, resulting in a light, disposable game you can play in forty-five minutes at the end of an evening without it ever getting old.

In theory.

Dominion is the game that kickstarted the current trend for deck-builders. It won a whole crapload of boardgaming awards on release and more-or-less set the paradigm for the deck-builders that came after it – everyone gets the same starting deck of some money and victory point cards, and they use the money to buy more cards from the supply in the centre of the table. This supply is randomly determined by drawing nine cards from a draft deck of about forty, with ten cards of each type drawn being placed into the supply. Once the game begins every player is free to build their deck in any way they choose provided they have the money in hand to buy new cards. Bought cards go on the discard pile, and once a player runs through their deck the discard pile is shuffled and forms a new draw deck.

Mechanically, Dominion is a work of genius. (It should be seeing all the imitators that have been released in the years since). Since your deck will recycle every time you run through it you’ll see all the cards in it multiple times, but how often you see them depends on how many cards are in it and how quickly you can run through it. If you’ve bought a really expensive card from the supply but your deck is filled with dross cards and you only run through it every five or six turns, then you will only get to use that card every five or six turns. This gives players a strong motivation to do one or both of the following:

- Remove weaker cards so that the deck becomes leaner and more efficient; you can’t help but draw good cards every single turn if that’s all your deck consists of.

- Get lots of cards that speed up the cycling process; many cards in Dominion allow you to draw more cards into your hand when played, allowing you to run through the deck more quickly.

The catch is that you can’t get rid of all your useless cards – at least assuming you want to win the game at some point – as the victory point cards have no function other than to be scored at the end of the game. Every victory point card you buy is potentially clogging up your deck with dead cards, making it bloated and inefficient. This is a neat mechanic which forces the player to strike a balance between total efficiency and actually scoring enough points to win the game, which is good because Dominion has nothing else going for it whatsoever.

Full disclosure time: I liked Dominion the first time I played it. I still like the central mechanic. It’s a very nice piece of boardgame design. Unfortunately Dominion makes no further effort to hook in the player. Many of the blog pieces I write tend to bang on about world-building in video games. It’s a quality I value very, very highly, and the same is true of board game themes. I can enjoy mediocre – or even downright bad – boardgames as long as they have an interesting theme that meshes well with what I’m doing as I play it, but Dominion’s problem is that it has a theme that doesn’t match the gameplay at all. The idea behind Dominion is that you’re supposed to be a king building a kingdom, and so all the cards are things you’d expect to find in a medieval town – village square, market, town walls etc. I forget what specifically is in the game, but that’s understandable since what the card is has precisely bugger all relation to what it does. The kingdom building theme is completely divorced from what is going on in the game, and to make matters worse this is a card game so you don’t even get the basic boardgame thrill of putting pieces down in front of you to get some visible sense that you’re developing your position. All Dominion has left to invest you in the theme is the card art, and this is by turns staggering bland and utterly dire. As a result it quickly becomes apparent that Dominion is an utterly soulless cipher with no joy or sense of fun to it whatsoever – that you are mechanically carrying out the same actions over and over again in the name of greater efficiency, which is a little too much like the real world for my tastes.

To make matters worse Dominion has compromised its major strength – that it is a standalone deck-building game with no additional investment required – by releasing a veritable horde of expansions, every one of which has somehow made the game worse in some way. These aren’t necessary as such, but if you’re getting tired of the base game and you want to get some new cards then you have to contend with ridiculous new mechanics like brewing potions and pirating ships. My breaking point came after the Seaside expansion, when I found myself staring at a game mat with my doubloons on it and thought “What the hell am I doing here?” The new cards came at the cost of making the game even more incoherent theme-wise, which is very bad for my continued interest in a game.

So I don’t play Dominion any more. When people ask me about it I refer to it in the same hushed tones that Alyx uses to talk about Ravenholm in Half Life 2 – it’s now this horrible, shambling, headcrab infested corpse-town that I don’t intend to ever visit again.

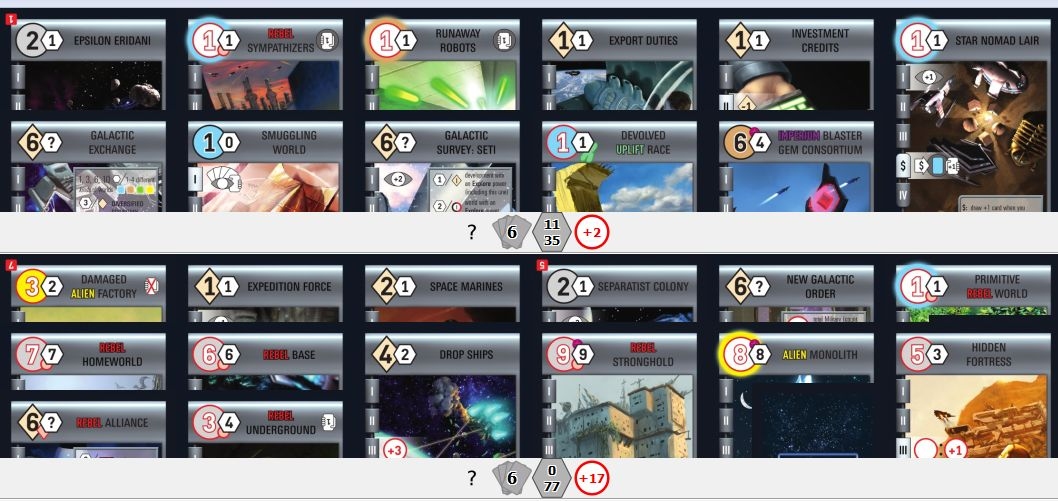

Race For The Galaxy (RftG) is a game that appeared just after Dominion, and couldn’t be more different. Where Dominion had a putative fantasy theme, RftG is decidedly sci-fi. Where Dominion insists on everyone having the same starting setup, RftG injects some unpredictability into the mix by giving everyone a unique starting homeworld that will, to a degree, dictate what strategy they pursue. Where Dominion allows players to pick and choose what they add to their deck, RftG has them drawing off of a single face-down supply so that they have no idea what they’re going to get. And where Dominion has discrete cards that are used for money, in RtfG every card is used for money. In fact RftG is a game that owes more to the action-based mechanics of Puerto Rico than it does a genuine deck builder like Dominion, but while it’s an interesting attempt to play with the format it is also ultimately a failure.

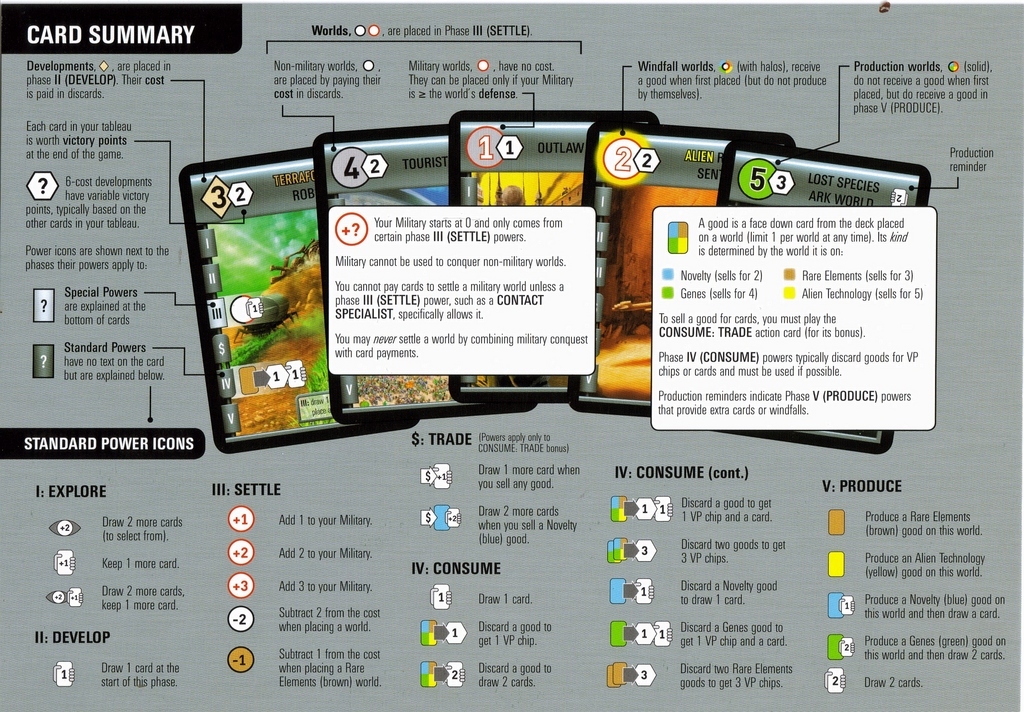

Starting from the top, the major hurdle facing a new player of Race for the Galaxy is the vast array of bewildering symbols that adorn every single card. When your game is so complicated that you can’t communicate what a card does on the card itself and have to resort to a collection of symbols that requires an A4-sized player aid filled with very small writing to decode, you know you’ve got a problem. You have to learn this highly specialised and esoteric language before you can even think about playing Race with any sort of ease or comfort, and that’s something that justifiably pisses many people off before they can get into the game.

(I just pulled the reference sheet from BoardGameGeek, and it turns out it’s actually double-sided.)

Once you’ve decrypted the symbols you’ll discover that RftG is actually a fairly bad game. I mentioned that every player gets a homeworld that dictates their strategy, but the problem is that in RftG “strategy” is a thing that is impossible. Any strategy you came up with would, at the end of the day, rely on you getting certain cards out of the random draw. Not only does this mean that you pretty much have to memorise the entire deck to know what is and isn’t possible, but it also makes winning contingent on a disproportionate amount of luck – especially since you’re not guaranteed to see a given card in the course of the game. Even if you run through the entire deck someone else might have used it as currency. The central draw supply ensures that the game is mired in this perpetual fog of uncertainty that makes it impossible to come up with any sort of coherent plan. It’s the deck building equivalent of blackjack.

I suppose one good thing about the game being so bad is that I was only mildly offended that there were cards included in the base game that basically didn’t work unless you bought (sigh) expansion sets. Despite this, though, I enjoy playing Race more than I do Dominion, and this is because Race connects with its theme far more effectively – you get to watch your space empire grow as you put planets down in front of you, and all these cards actually do something. I am not going to outright condemn a game which lets me pretend to be Emperor of the Galactic Imperium and send in the Space Marines to eradicate the Rebel Homeworld even if winning it is based entirely on the luck of the draw. So if somebody ever puts a gun to your head and forces you to choose between playing Dominion and playing Race for the Galaxy, pick Race for the Galaxy. It’s a rubbish game, but a better experience just so long as you don’t take it too seriously.

That’s the two awful deck builders dealt with. Next week I get to tell you all about two deck builders I actually enjoy: Thunderstone and A Few Acres Of Snow. Bet you can’t wait.

My breaking point came after the Seaside expansion, when I found myself staring at a game mat with my doubloons on it and thought “What the hell am I doing here?”

lol.

[...] Being the second half of a roundup of the various deckbuilding games you can buy these days. First half here. [...]

Race for the Galaxy is not a deck builder. Race for the Galaxy is objectively not a bad game. This review is not objective.