Mars Horizon is a modern take on Buzz Aldrin’s Race Into Space. Is it really any surprise that I had it bought and downloaded fifteen minutes after it released on Steam?

It is, unfortunately, not anywhere as good as the statement “a modern take on BARIS” implies. Like BARIS, Mars Horizon is a boardgame-esque light strategy game about managing your chosen country’s space agency through the trials and travails of the Cold War-era space race. Unlike BARIS it doesn’t stop with the Moon landing, though; as you might have guessed from the name, the end goal of Mars Horizon is to land a group of astronauts on Mars instead. As this is not a thing that has actually happened in real life yet it gives Mars Horizon a much broader scope, since instead of focusing on the twelve eventful years from 1957 through to 1969 it can instead do the entire history of space travel to date, including space stations, space shuttles, space telescopes, outer planet flybys, the Grand Tour, Mars landers, and even a Pluto flyby if you’re willing to wait the requisite 13 years. It doesn’t project too far into the future with the only properly sci-fi mission you can do being the Mars shot itself (Mars Horizon does unfortunately buy into the PR guff saying that a manned Mars landing is just around the corner, which quite overlooks the fact that it’s been just around the corner for the last 25 years) but just by pushing the end date forward by another half-century Mars Horizon is, in theory at least, a game with a lot more body than Buzz Aldrin.

Mars Horizon is quite determinedly ahistorical. It starts in 1957 just before the historical launch of Sputnik, but a slightly weird thing that it does is to include ESA (Europe), CNSA (China) and JAXA (Japan) along with the US and USSR as playable entities from this date, and assumes that (for example) the Chinese could have been working on their Long March rockets at the same time as the US was having their Vanguards repeatedly blow up on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral. This is a fine concession to make in the name of competition, and I think Mars Horizon would be much worse off if it just restricted itself to the US and USSR as BARIS did; half the fun of these games is plotting out an alternate history where the Space Shuttle actually worked as intended, the sole achievement of the N1 launch booster wasn’t creating one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, and humanity didn’t lose interest the Moon approximately five seconds after Neil Armstrong climbed back into the Eagle lander, and so it’s absolutely no problem to extend those what-if scenarios to Europe, China and Japan having the industrial capacity and expertise to compete in the space race also.

Instead my problem here is that I don’t think it goes quite far enough, as while Mars Horizon is happy to postulate the involvement of other space agencies it’s less gung-ho about inventing bespoke rocket technology and spacecraft that would make each agency meaningfully different. If you look at the research tree for NASA’s rockets it’s precisely what you’d expect: Jupiters, Titan IIIs, Delta IVs, Saturn Vs, and so on. Boot up a game as JAXA, however, and you’ll see that 90% of the tree is identical; they get maybe half a dozen unique rockets as well as their own variant of the Space Shuttle, but the rest of it is Jupiters, Titan IIIs, Delta IVs and Saturn Vs. It gets worse when you try a game as the USSR, as for some reason they also get access to Jupiters and Titan IIIs despite having a larger set of native rockets such as Soyuz and Vostok launchers. The generic nature of this tech tree is extremely unwelcome, especially since there’s zero difference between a Viking upper stage and a Long March I upper stage anyway; it’s effectively just the barest of cosmetic sops to theming your space agency, and in practice they all play identically except for some passive bonuses that are set when you start the game, like ESA benefiting more from joint missions with other space agencies and the USSR not suffering any loss of public support when a rocket explodes mid-launch and incinerates a trio of cosmonauts. I appreciate that Mars Horizon is an indie game and that coming up with five completely different, nationally-appropriate tech trees is a big ask, and that it’s probably a feature that’s better off being cut if you don’t have the resources or development time to make it work, but I also think that Mars Horizon not doing this is one of several missed opportunities that drastically reduce the replayability of the game. I’ve finished a campaign as the USSR, and I don’t feel like starting another one as ESA or CNSA because I don’t think it would be meaningfully different to my first time though.

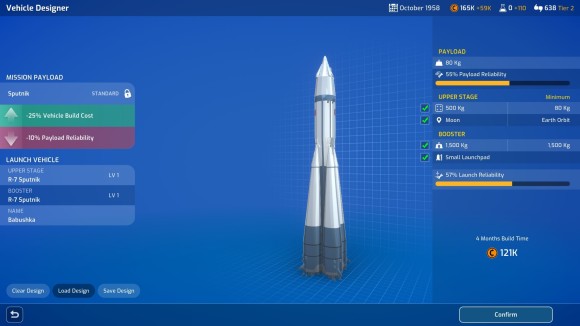

Still, the basic concept behind Mars Horizon remains compelling: planning and launching space missions to hit critical milestones (first artificial satellite, first Moon landing, first space station etc.) that generate public support to increase your funding, as well as the science that you need to research newer, more expensive rockets that are capable of lifting the heavier payloads required to extend your reach further into space. The mission is the basic unit of work in Mars Horizon, and you start the game with a single Mission Control building in your HQ that gives you the capacity to plan and execute a single mission at a time. A mission isn’t just a matter of saying you want to fire some rockets into space and then watching it happen… well, okay, it is, but the main factor to consider here is that it isn’t instant. Nothing in Mars Horizon happens straight away. Take launching Sputnik, which is the simplest mission in the game: you cannot even start this mission until you’ve researched both the mission and the payload. This takes some time. Once you’ve spent several months doing that, you can start the Artificial Satellite mission, the first step of which is building the payload you just researched. This takes some more time. Then you have to build the launch vehicle by matching together an upper stage and a lower stage capable of carrying Sputnik into orbit. This takes even more time, and I really hope you actually finished researching the appropriate launch vehicle components while the payload was building because otherwise your mission is going to stall with a payload that can go nowhere. Then, once you have both a payload and a launch vehicle, you have to select a launch date; this is a minimum of one month in the future, and you might even want to punt it forward by a few months so that your mission staff can undergo additional training to maximise the odds of success or boost any mission rewards.

Finally, after many months of effort (or five minutes of in-game time if you’re hammering that Next Turn button), your Sputnik is ready to launch. Bear in mind that your single Mission HQ has been fully occupied with this mission from the moment you started building the payload; you cannot do anything else mission-related while Sputnik is on the table, at least until you build a second Mission HQ. Assuming the launch goes successfully and that Sputnik doesn’t malfunction, that’s the end of that mission since Artificial Satellite — and most missions that take place in the vicinity of Earth, including Moon missions — have flight durations of less than a month, and so finish instantly in game terms. If you’ve set up a mission where you’re flying to Venus or Mars, though, the in-game flight times are roughly equivalent to the real life ones, meaning that your Mission HQ and its associated mission slot is going to be locked up for an additional 4-8 months while the spacecraft reaches its destination. And if you’re flying to one of the gas giants — or god forbid, Pluto — you had better be prepared for that mission slot to be unavailable for an actual, literal decade as your probe painstakingly makes its way to the outer edges of the Solar System.

Still, that kind of mission is some considerable way beyond what your fledgling space agency is capable of at the start of the game. Right now you just get about getting something into orbit as quickly as possible, and ideally ahead of most or all of the other space agencies who are trying to do the same thing as you get a reasonably hefty bonus for being first. If your Sputnik launch has been successful then you’re going to be rewarded with two forms of currency: Science, which is used to research new technology, and Support, which is a numerical representation of how much public support your space program has and which will award monthly funding increases once it exceeds various tier thresholds. You plow the Science back into researching new mission types and launch vehicles and base facilities, while the Support passively ticks up in the background — it will never decrease unless a launch fails, so any Support rewards directly translate into more cash money for you.

This is the core loop of Mars Horizon, then: launch missions to get Science income and increase your money income via Support, which lets you research and build bigger and better rockets that let you launch more ambitious missions to get even larger quantities of Science and Support, which are then invested straight back into rockets and spacecraft. Interestingly your base Science income — the Science income that you get if you don’t launch any rockets — is almost non-existent; there’s a building in your HQ that generates a residual amount that is sufficient to research the things you need to launch Sputnik (although if you actually want to beat the other agencies you’ll need to supplement that basic Science income by launching sounding rockets for atmospheric measurements), but after this research costs increase exponentially and you have no way of increasing your passive income to keep pace. In the mid-to-late game, 99% of your Science income is coming from the missions that you launch, so if you don’t have any on the go — if you’re bottlenecked by money issues or launchpad logjams — then your research can end up completely stalling out. Similarly if you focus too much on Science income at the expense of Support you won’t increase your funding fast enough to be able to afford the shiny new rockets you’ve been researching, so there’s no point beelining for a milestone that’s some way down the tech tree if you don’t have the financial base to support it.

Balancing the three factors of time, money and science so that you’ve built up enough money to build a new rocket at the exact same moment as the research finishes and a mission slot becomes free is quite a pleasing brain-teaser. This exercise of sequencing and parallelisation (you can research and build up to three more Mission HQs, allowing for four missions on the go simultaneously) and extremely long-term planning (there are missions in here that take one fifth of the entire game to finish) is the thing that Mars Horizon does very, very well. It properly gets across that you need to be planning your future research and rocket launches on a timescale of at least half a decade, if not more. I almost never found myself researching something for the hell of it, since the limited resources available and the constant race against time to beat my rival space agencies to whatever the next milestone was always dictated that my resources be invested only in things that helped me towards my ultimate goal of landing on Mars.

Alas, this was less of a pragmatic choice than it first appeared, since the tech tree is deceptively limited; you get a choice of 4-6 rocket boosters at each tier of the Rocket research tree, but really you just need one lower stage and one upper stage capable of carrying the corresponding payloads for that tier. You get a choice of whether to research a Uranus flyby mission or a Neptune flyby mission, but there’s not much in-game difference between the two (the Neptune flyby yields a bit more Science but takes slightly longer) and both of them take you one rung further towards the Mars missions. It was only in the Base research tree that I found myself properly weighing up whether researching an astronaut centrifuge or a space plane runway was worth the Science cost, since few of the base buildings are linked to unlocking new things and the vast majority of them simply provide useful passive bonuses that reduce costs and boost mission rewards — these bonuses are relatively small, which I usually hate, but this is a game about long-term planning and if a building can pay for itself in five years then it’s pure profit for the next two decades; trying to figure out which ones offered a decent return on investment were the only really meaningful technology choices that Mars Horizon offered me.

Nevertheless, Mars Horizon’s research and mission scheduling side offers enough plate-spinning that it almost makes a decent project management simulator. If you’re the sort of rather odd person who finds making GANTT charts satisfying — and I cheerfully include myself in that description — then it’s probable that you’ll end up quite enjoying Mars Horizon for that alone. It shares a lot of brainspace with worker placement games such as Agricola in that regard, which is why it reminds me much more strongly of a boardgame than BARIS did1, and since I happen to love worker placement games this strong resemblance was what kept me hooked through most of the 17 hours it took me to land some cosmonauts on Mars. And it’s a damn good thing for Mars Horizon that this is so, because I found nearly all of its more videogame-y systems to be by turns insubstantially light and actively self-defeating.

Take rocket launches. Like BARIS, Mars Horizon abstracts the success or failure of launching a rocket down to a roll of a D100. Your rocket has a reliability rating percentage which is subtracted from 100 to create a success threshold which you need to roll higher than on the D100 for a successful launch — so a rocket with a reliability rating of 60% would need to roll higher than 40. However, Mars Horizon is much more forgiving than BARIS, and further subdivides the result range below 40 into two outcomes. Rolling 10 or below is a critical failure that results in the rocket exploding, just as with BARIS, but rolling 11 through to 40 simply results in some mechanical problem that imposes a very minor penalty in the payload minigame that follows on from the launch. I never cared about this penalty; every single one that I saw was so slight that I always fulfilled the mission objective with time and resources to spare, which meant that this supposedly unreliable 60% launch rating was, in practice, a solid gold 90%. Mars Horizon treats launch reliability as a big deal, and gives you a choice between researching more expensive rockets with a higher starting reliability rating, and less expensive rockets that are unreliable and which you should, in theory, have to improve over time by accruing launch experience. However, because money is so tight and because the difference between the critical failure thresholds for a 60% reliability rocket and an 80% reliability rocket is something like 5%, I always picked the cheapest one. The same goes for waiting for optimal launch windows; launching during a suboptimal window imposes a penalty of 15% to launch reliability, but this just raises the critical failure threshold by a couple of percent. The chances of actually losing a rocket are so laughably small that I completely ignored launch reliability as a factor for most of the game and lost three out of a hundred launches. Three. That’s how many rockets I’d have to watch blow up just to get a single successful outcome in BARIS.

Now, I am not particularly complaining about Mars Horizon not being as difficult as BARIS, as BARIS was a bastard hard game even on the easiest difficulty setting. I do think there’s a happy medium between the punishing success odds of BARIS and the utterly toothless implementation in Mars Horizon, however, since it renders the rocketry side of the game almost totally irrelevant. The innate launch reliability of each rocket model? Doesn’t matter. Doing unmanned test launches to raise the reliability to the point where you’re happy to strap astronauts on top of them? Don’t bother. Waiting for the best launch window, or doing pre-launch training to improve the odds of a successful launch? Absolutely pointless. Pissing it down with rain on launch day, which dumpsters your launch reliability rating even further? Who cares? None of it is anywhere near enough to disincentivise building the cheapest, most unreliable pieces of shit you can and throwing them up the gravity well on the first available launch date, so that side of the game just might as well not exist. Which is a stunning thing to say about the “launching rockets” part of a game about the Space Race.

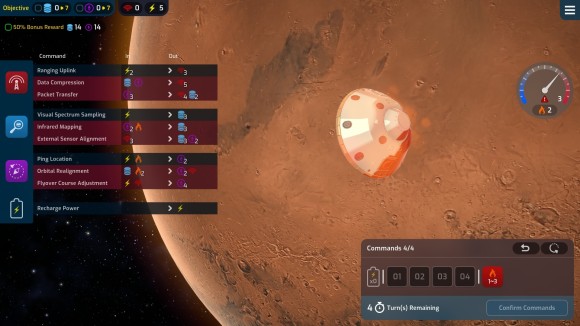

The actual mission gameplay has an altogether different problem. Once it’s successfully launched into space (and it will always successfully launch into space) the payload undergoes a series of mission phases — so an Artificial Satellite has just one phase of achieving Earth orbit, while landing on the Moon would have four phases: burn to the Moon, achieve lunar orbit, lander descent, and then burn back to Earth. No matter what the mission is, though, each phase of it is represented by the same resource-shuffling minigame. There are three core resources: Communications, Navigation, and Data, along with a special Energy resource. You have a number of actions per turn, and a number of action choices for exchanging resources for other resources — one Energy for three Data, two Data for three Navigation, one Data and two Navigation for six Comms, and so on. You’ll be given a target value to hit for any or all of the core resources, but you start with none of them. All you have is your spacecraft’s Energy reserves, so you start by converting that into Navigation (for example), and then some of that Navigation into Data and Comms, and then some of that Comms into Data again; if you can make the right choices and chain these conversions together in the right order, you’ll hit the target thresholds and the mission phase will be successful and you move on to the next one. If you fail to hit the targets by the end of your final turn, however, the entire mission fails outright.

This is a much more consequential failure penalty than the one attached to most of the “failed” rocket launches, and so the performance of your spacecraft — and yourself during the minigame — matters. Your payload spacecraft has a reliability rating just like your rockets do, and once you’ve locked your actions in for the turn the game rolls a D100 to gauge the success or failure of each one. A success means it works as advertised, while a failure makes that action either more expensive or return less resources. Given that brute-forcing the calculations is rarely possible and that you need to be quite precise with your arithmetic and action-chaining to make the target totals — and that not having enough resources to perform an action means that action is entirely wasted — this is a bigger deal than it sounds, especially given that there’s no half-measures this time: the standard spacecraft has a 30% chance of failing any given action, and you can only mitigate it by spending your limited Energy reserves to protect against the penalty. Making sure you have enough Energy to cover potential failures is a big part of this minigame — sometimes a failure will cost you a resource you don’t need and you can get away with taking the hit, but on other occasions it might cost you the rest of your turn if you don’t spend an Energy to absorb the damage.

As it stands, this is not the worst minigame I’ve ever seen; there is a significant RNG element to it with the D100 rolls but Mars Horizon provides a tool to mitigate that with the Energy resource so it’s nowhere near as obnoxious as it could be. It has precisely sod all to do with space travel — even the theming is bad — but it’s the sort of thing that I don’t mind playing a few dozen times over the course of the game. The problem here, though, is that I didn’t play it a few dozen times. With a hundred missions launched over the course of my campaign, most of which had multiple phases, I must have had to sit through it a couple of hundred times because Mars Horizon uses it for every single mission in the game. Oh, you’ll have to deal with additional factors depending on what the mission is — so for the Moon landing there’s a Drift resource you have to keep within a target range, and for the Venus probe you have to keep Heat levels under control, and if you do a Jupiter flyby you’ll have to minimise Radiation that can damage your probe if it’s not completely flushed at the end of each turn — but it’s the same minigame at the heart of it each time, with the same basic strategy applied to each one. I keep saying this, but there’s no minigame in existence that can survive that amount of repetition. There is an option to auto-resolve instead of having to sit through the minigame, but it’s here we run into a second issue: Mars Horizon offers huge boosts to the mission rewards — on the order of +50% — for doing particularly well in the minigame that you won’t get if you auto-resolve. Because your science and funding income is the biggest constraint on what you can do in the planning side of the game, a boost of 50% to both of them cannot be ignored. I felt like I had to suffer through the minigame in order to give myself the best chance of winning the race to Mars, despite having grown desperately bored of it long before the end of my campaign.

So when it comes to the detail Mars Horizon is oddly split between being nowhere near important enough to engage me and being so important that I couldn’t disengage from it even though I wanted to. I deeply wish these parts of the game were different; that there was a bit more crunch to the rocket launches to keep me engaged, and that there was a bit more flavour to the mission phases to keep me from becoming thoroughly sick of it. This latter failing is a somewhat curious one given that Mars Horizon is part-funded by ESA and is supposed to have edutainment somewhere within its remit; while it does have some nice (albeit low-budget) sequences of probes flying past gas giants, landers descending to the Moon, Space Shuttles on re-entry etc. etc., it’s startlingly light on the actual background behind all of these space missions that you’re embarking on. At most you get a two-sentence explanation of what each mission is, and no explanation of what each mission phase is; there’s next to no effort made to anchor those repetitive mission minigames in reality, to pretend that they’re anything more than shuffling numbers around. Mars Horizon instead chooses to sequester most of its science background away inside an in-game “Spacepedia”, which as far as I could see consisted of single-paragraph articles that were essentially a precis of the corresponding Wikipedia article on the subject. Unfortunately the link between gameplay and the Spacepedia is non-existent; there’s no way to directly access (for example) the article on the Venera probes from the Venus mission screen, and anyway if I wanted to read a Wikipedia article I would just go to Wikipedia. This is a video game, and there are several ways Mars Horizon could have chosen to inform and educate the player that are far more organic — tooltips, mission briefings, trajectory visualisations in an in-game Mission Control, I don’t care, just pick one that’s not actively directing me out of the game to read a block of text.

Despite all of that, I still don’t feel quite as actively contemptuous towards Mars Horizon as I have towards other recent releases. The core loop of mission planning, launching and reward investment into new missions is extremely solid, and while I do not think it’s solid enough to compensate for the game getting nearly everything else wrong it is at least enough to make me give it the benefit of the doubt. I’m prepared to overlook quite a lot given Mars Horizon’s budget price (£15 on Steam), and while it ended up testing the boundaries of my patience beyond even those broad limits I genuinely did enjoy the majority of my time with it in spite of all of its flaws. It was only during the last few hours of the campaign that those flaws really started to become insufferable, and while I’m never going to play a second one that’s means I still got 10-12 hours of decent gameplay out of it. I definitely feel like it’s an extremely niche game, though, one that’s only going to appeal to a very specific subset of people who enjoy space-themed project management games, who are willing to put up with some extremely wonky design and who have a high tolerance for minigames. If that doesn’t sound like you then I think you’re better off staying clear of this one.

- Which is ironic, considering that BARIS itself was based on a boardgame called Liftoff! ↩

I think the saddest thing with this game is the repetitive nature of missions, if they could have made some minigames different the game would have been leagues above what it curently is. I.E they could have made liftoff a kind of fly trough the rings minigame where stuff tend’s to either set you off course or break part of your spacecraft. They could have made docking into a timing and alignment minigame where if you fail your astronaut need to spend another orbit in space and perform poored during subsequent task’s. The reentry could halso have been a game of balancing heat with direction so you don’t drift too far from the landing site.

The repetition is indeed a major problem. Past the early game, I auto-resolve all missions and stick mostly with standard rewards.

However, the different space agencies and rockets are not as similar as you suggest, especially as the game gets more difficult in the midgame. For example, China has reduced building upkeep and building cost and the difference can be a lot of money. Japan has really powerful contractors that either boost science or save a lot of money on rockets, allowing you to throttle up or down to match your available mission slots. Mars Horizon doesn’t let you fail outright, but especially in the midgame, playing to the agency perks is critical to not stalling out.

The rockets are also not as similar. It’s true that the tech tree is quite similar for all agencies, but looks are deceptive. USSR gets to launch all early game payloads with one set of components, but pays for that convenience when the R7 overperforms for the mission requirements. The agency-specific rockets also have different build times and costs. The most extreme example is China, which can farm manned moon missions easily with their Long March 2F. It doesn’t seem like much on first glance, but the price and time difference between a Saturn, N1, and the Long March 2F makes a huge difference in how much the mission is worth. The Jupiters and Delta IVs, while available to everyone, are actually suboptimal choices, costing more and taking longer to build.